Selling Puts

The Ultimate Guide for Put Sellers

of All Experience Levels

Selling puts is, hands down, my favorite investing strategy because it offers great returns while being enormously flexible and forgiving.

When approached sensibly, it's also MUCH safer than owning the underlying stock.

In this comprehensive and free resource, we're going to cover everything you need to know about selling put options safely and successfully.

Be sure to bookmark this page because you're going to want to come back to it again and again (and also consider sharing it with friends and family you believe would benefit from it).

Specifically, here's our table of contents:

- Chapter 1 - Put Selling Basics and Overview - What is a put option, how do you sell a put, and why would you want to?

- Chapter 2 - Selling Puts for Income vs. Selling Puts to Buy Stock at a Discount - There are only two viable reasons to sell puts - your job is to be clear on your purpose so you can then focus on maximizing your efforts.

- Chapter 3 - Best Stocks for Selling Puts - In this section, we look at important specific criteria when selecting an underlying stock on which to sell puts along with whether it's better to sell puts on value stocks or on growth stocks.

- Chapter 4 - How to Find Great Put Selling Trades - In Chapter 3, we looked at the type of stocks that are best for selling puts (and the type of stocks that aren't). In this chapter we're going to look at the specific conditions that represent attractive put selling set ups as I show you precisely how I go about finding great put selling trades.

- Chapter 5 - Best Position Size When Selling Puts - How many naked put contracts you sell when initiating a trade is vitally important, and in this section, I share what I believe is the best guideline for position size, why this guideline has served me well, and why you don't need to be overly rigid when using it.

- Chapter 6 - Managing, Adjusting, and Repairing Naked Puts - Being able to find great put selling trades, and knowing when and how to set them up, is only part of the battle. You also need to know how to most effectively manage your winning trades and how to safely repair your losing trades.

- Chapter 7 - Bonus Put Selling Resources - Want even more? This section includes a comprehensive collection of links to original articles covering all aspects of the put selling process. Enjoy!

Chapter 1 - Put Selling Basics and Overview

There are basically two reasons to sell put option contracts - to generate income or to acquire shares of a stock at a discount to the current market price.

We'll look at these two rationales in more detail in Chapter 2, but if you're new, or relatively new, to option trading, this chapter is about quickly getting you up to speed on the basics of put selling.

What Does it Mean to Sell (or Write) a Put?

The standard definition of a put option contract is that a put gives the holder (or buyer) the right to sell 100 shares of stock at a specific share price by a set date.

Basically, there are two ways of viewing short puts (i.e. the strategy of selling puts):

- Being paid to insure someone else's stock

- Being paid for offering to buy someone else's stock

I really like the insurance analogy. It translates well because puts are basically insurance for the share price of a stock.

Example: If you own 100 shares of XYZ and you purchase a put at the $30 strike price, you can exercise your contract up to the expiration date and "put" the shares to the put seller at $30/share.

In other words, you're insured at the $30 share price level - no matter how low the stock trades, you can exercise your contract and force someone else to buy your shares for $30/share.

As a put seller, that makes you the insurance company.

Ah, insurance - how boring, right?

Not in my view - especially when this form of insurance can be both lucrative and safe as we'll see.

But first, let's look at some key definitions and examples . . .

How to Sell a Put - Key Terminology

Like a lot of specialized topics, option trading has its share of jargon, but once translated into English, it's actually very easy to understand.

Here's the key terminology you need to know:

UNDERLYING - This simply refers to the underlying stock that you're selling the put against, be it Coca-Cola (KO), Microsoft (MSFT), Johnson & Johnson (JNJ), or any other optionable stock.

STRIKE PRICE - This is the price at which you're "insuring" the underlying stock. If the stock is trading at or above this price at expiration, the put will expire worthless. If it closes at expiration below the strike price, you will automatically be assigned the shares (these are basic definitions - later we'll explore the incredible flexibility of managing short options).

EXPIRATION DATE - As you might expect, this tells you the duration of the trade - just as a traditional insurance policy is only valid for a specific time frame, option contracts also have finite ending dates. Depending on the stock, you can select weekly expirations to options that don't expire for more than two years.

PREMIUM AMOUNT - This is the fun part, how much you get paid. Option prices are listed in what's called an Options Chain which includes the market makers current bid and ask prices (just like stock quotes) - but since each contract represents 100 share of the underlying stock, to convert to total dollar amount, you'll need to multiply these prices by 100 for each contract you're trading (if you sell a single put for $1.25/contract, for example, you would collect $125 up front before commissions).

ASSIGNMENT - When the owner of a put exercises his or her contract, someone is on the other side of that transaction being assigned the shares - i.e. acquiring the shares at the agreed upon strike price (being assigned the shares - especially prior to expiration - is one of the biggest fears of those newer to the strategy, but it's often an overblown fear, easy to avoid, and easy to deal with if it does happen to you).

Entering a Short Put Trade

There are four basic order transactions when it comes to option trading, and this can be confusing if you're new (or even not so new) to options, but fear not, I have you covered:

>> Buy to Open

>> Sell to Open

>> Buy to Close

>> Sell to Close

(These four babies are the building blocks of even the most sophisticated, multi-legged option strategy.)

For the sake of our discussion here, when we sell a put, we submit the order as a Sell to Open order.

Put Selling Tip!

The Sell to Open transaction can throw newer option traders, but let's think about this . . .

Selling something you don't own creates a short position (hence when you sell to open a put option, you've established a short put position).

In one way, that's similar to shorting stock, but where it can be confusing is that short sellers benefit when a stock declines while put sellers benefit the most when a stock doesn't decline.

Selling a put is also referred to as writing a put, and I find this can be a more helpful way of viewing the trade because it aligns more closely to the insurance analogy.

You're writing a put in the same way that your insurance company writes an insurance policy which you then sign and buy.

Keep in mind - whatever gets opened must eventually be closed.

So a Sell to Open (put selling) transaction will eventually be closed in one of three ways:

- The put expires worthless (if the stock closes at or above the short put strike price at expiration)

- The put holder exercises the option (and you are assigned the shares)

- You submit a Buy to Close transaction

This last one is where the great flexibility of put selling starts to come in - because you are always free to buy back the put you previously sold or wrote at any time.

There are different reasons why you might want to Buy to Close a short option - cutting your losses on a trade, exiting early to lock in profits, or as part of a roll or adjustment.

We cover all this in great detail in Chapter 6 on managing and repairing short put trades.

(For the record, the trade management and trade repair system I've personally developed is so battle proven and effective, it's extremely rare that we would ever give up on a trade and book an overall loss.)

And just to make sure we're clear, these opening and closing transactions are reversed if you're a buyer of calls or puts.

You begin with a Buy to Open order and end with a Sell to Close order (unless, again, the option expires worthless or you choose to exercise it at some point).

Example of Selling a Put

The easiest way of getting all this down is for us to walk through an example.

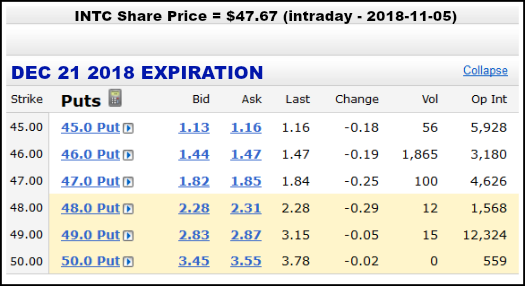

Here's a screenshot of the option chain for INTC (Intel Corp) intraday on Monday, November 5, 2018:

The above is from TDAmeritrade.

Every broker and website that publishes option quotes will have their own unique look to their option chains, but they all contain the same core information:

The above is also just a snapshot.

A full chain would include multiple expiration cycles along with quotes for both calls and puts.

And each option expiration cycle will have many more strike prices available than what's included above (these are "at or near the money" - meaning these are strikes that are closest to the current share price of the underlying stock).

So let's say that you don't believe that INTC will trade lower in the near term, OR that you would potentially like to acquire shares at a little lower price than where they are currently trading.

(Again, we'll go into more detail in Chapter 2 about selling puts for income vs. selling puts for stock discounts).

So you decide to sell or write an INTC DEC 21 2017 $47 PUT for $1.82/contract.

A few points to make sure we're on the same page:

#1 You sell options at the bid price (e.g. SELL TO OPEN a new position or you SELL TO CLOSE an existing position).

#2 You buy options at the ask price (e.g. BUY TO OPEN a new position or BUY TO CLOSE an existing position).

#3 Always submit your orders as limit orders and try to get better pricing than what's quoted on the option chain when it makes sense.

With the INTC example, the bid-ask spread is actually pretty narrow ($1.82-$1.85), so if I were selling the $47 put, I would simply enter the order as a SELL TO OPEN limit order specifically at the $1.82/contract bid price.

In other situations, the bid-ask spread on an option you want to trade may be a lot wider.

If, for example, the bid-ask quote was $1.80-$2.00, then I would submit my Sell to Open order for $1.85/contract and there's a good chance I'll get filled at that price (or better, depending on your broker).

#4 With a SELL TO OPEN short put trade @ $1.82/contract INTC example, you receive $182 in cash after your order is filled.

Minus commissions, of course - and that will vary according to your broker.

Commissions do add up.

Depending on how much you trade, going with an online broker with extremely low commissions (such as Tastyworks or Interactive Brokers) can literally save you - or boost your returns by - hundreds of dollars per month.

Chapter 2 - Selling Puts for Income vs. Selling Puts to Buy Stock at a Discount

Any time the topic of selling puts comes up, you're almost always guaranteed to hear someone say something along the lines of:

"Only sell puts on stocks you don't mind owning."

Please. What does that even mean? That's like saying you should only sleep with people you don't mind marrying.

Huh?

How does that improve your dating life OR your prospects of finding a soul mate?

The first piece of put selling advice you should take to heart is this:

Know exactly why it is you're selling puts in the first place.

And there are only two viable reasons . . .

Reason #1 - Selling Puts for Income

As we've already discussed, selling or writing puts is often compared to being your own miniature insurance company.

But instead of insuring someone else's car or house or life, you're insuring the share price of their stocks.

If the stock in question cooperates, you can make some very good short term returns.

And this has nothing to do with owning the shares.

When Allstate or State Farm or Geico insures your car, it's not a clever ploy on their part to gain possession of your vehicle at a less than fair market value.

They're simply trying to turn a profit.

If you're primarily drawn to put selling because of the great short term income the strategy can produce, don't feel guilty about that.

And you don't have to limit your put selling "clients" to only those stocks that you think others would approve of as suitable long term investments

At the same time, since it is about making money, quality does come into play, as does a number of other factors that you want to line up in your favor as much as possible (which we'll look at in Chapter 3).

And inside the Leveraged Investing Club - specifically, in the training included in the Sleep at Night High Yield Option Income Course - we take things a step (or three?) further.

The Course and Club (when periodically available), don't just show you how to sell puts as though you were a generic insurance company.

Not in the least.

I show you how to transform yourself into "The Insurance Company from Hell" where your objective is to collect lots of premium and then avoid like the plague ever paying out a claim.

(Which I define as either buying back your short puts for a loss or allowing yourself to be assigned the shares against your will.)

When you have the necessary clarity, you discover that selling puts is not just a forgiving strategy - it's amazingly flexible one that allows you to repeatedly "renegotiate" the insurance policies you write to your advantage

As many times as it takes.

There are no guarantees about anything in life, but it's extremely rare that we ever book a loss at the end of the day selling puts.

I call it Heads You Win, Tails Mr. Market Loses, and we'll look more closely at managing and repairing short put trades in Chapter 6).

So there's no shame in selling puts for current, high yield income - and with no intention or willingness on your part of ever owning the underlying shares.

But if you do like the idea of outsmarting Mr. Market and acquiring shares of a stock at a steep discount, put selling can be a powerful way to do just that.

Reason #2 - Selling Puts to Buy Stocks at a Discount

First, a disclaimer - I'm not talking about generic put selling here.

Selling puts to acquire stock at a discount is often explained in a very basic, very superficial way - which, at best, results in small, one time discounts.

This Investment U article is pretty representative of that superficial approach.

Basically, this standard, wishy-washy approach involves writing or selling an out of the money put (i.e. at a strike price below the current share price and "at a price at which you don't mind owning the stock").

>> If the stock is trading at or above the strike price of your short put at expiration, the put expires worthless and the cash premium you received when entering the trade is yours free and clear.

>> And if the stock is trading below the strike price at expiration, you will be obligated to buy the shares at the agreed upon strike price.

But your effective cost basis on those shares is calculated by taking your purchase price at the strike price less the initial premium you collected.

Say you sell a $30 put (i.e. at the $30 strike price) on a stock for $0.50/contract (or $50 total since each contract represents 100 shares of the underlying stock).

If assigned (and excluding commissions), your cost basis on the shares would be $29.50/share:

- $30/share times 100 shares = $3000

- $3000 less the $50 option premium you collected = $2950 net purchase price

- $2950 net purchase divided by 100 shares = $29.50/share adjusted cost basis

Presto, a small one time discount.

So What's the Problem?!?

Actually there are three problems with this overly simplified put selling approach.

>> First, by selling at out of the money put, you're collecting a relatively minor amount of premium.

The farther away the strike price is from the current share price, the less time value is included in an option's value, and at the end of the day, as an option seller, what you're really selling is time value.

(Time until expiration is another factor, of course - here's an important 3 part series on Best Durations When Buying and Selling Options.)

>> Second, the potential "discount" on an out of the money short put is often overstated because it's frequently calculated based on where the stock was trading at the time you entered the trade.

So if you sell a $30 put when the stock is trading @ $35/share and you end up with a $29.50/share adjusted cost basis, that's an impressive discount, right?

Actually, it's not.

Because whatever "discount" you generate is coming mostly from the decline of the share price - not the premium you collect and deduct from the strike price paid on assignment.

And if the stock is trading a lot below $30/share (which is what triggered the assignment) then your "discounted" $29.50 adjusted cost basis is likely going to be a lot higher compared to stock-only investors who bought shares after the stock dropped.

>> And third - what drives me battiest about these superficial explanations is the brain dead assumption that these short put trades have to be one time, binary events.

They're not in the least, and as we'll see in Chapter 6 on trade management and repair, the ability to switch from a single trade mindset to a campaign mindset will put you miles ahead of the generic traders.

But the way this approach is almost always dumbed down and illustrated, it's a one shot trade from a very small caliber weapon.

How to Get Big Discounts on a Stock When Selling Puts

OK - if selling puts simplistically for small, one time discounts doesn't cut it, then what does?

How do you go about using the strategy to get legitimately big discounts on your favorite stocks?

It's a simple mind shift where you go from viewing these as one time trades, and thinking of them instead as a potential campaign or series of trades.

(When selling puts for income, the majority of your trades likely will be one time trades, but if you're truly seeking to buy stock at big discounts, the campaign mindset is essential.)

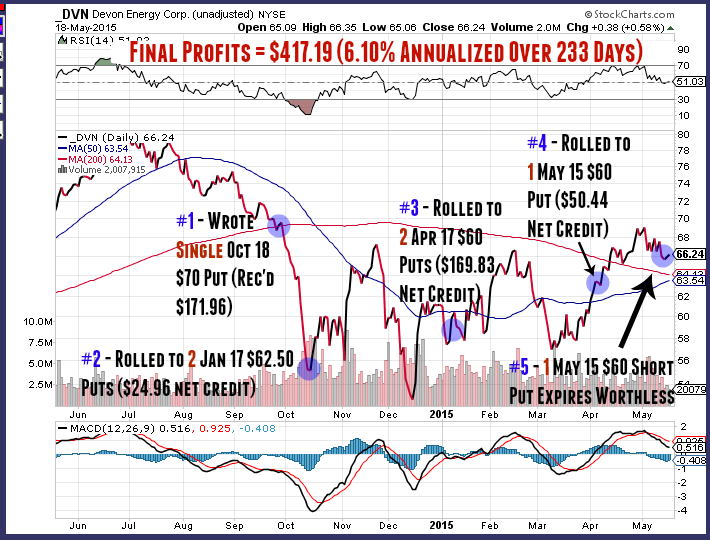

Collecting Premium Multiple Times on the Same Trade

With a put selling campaign, it's still a single trade in a way. It's just that the trade has multiple points (or legs) that repeatedly bring in additional premium.

We'll look at rolling and adjusting your short put trades more in depth in Chapter 6 on Put Selling Trade Management and Repair.

But the ability to roll a short option position for a net credit - i.e. to collect more in new premium for setting up a new trade at a later date than what it costs you to buy back or exit your old, expiring position - is arguably the most important advantage you have as an option seller.

Let me show you what I'm talking about . . .

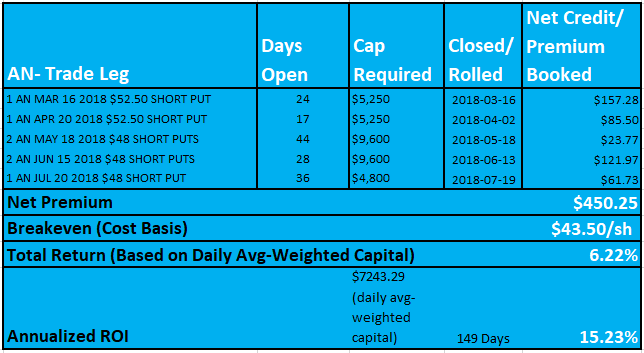

Below is a Trade Performance Table on an AutoNation (AN) naked put campaign I traded inside the Leveraged Investing Club during the spring and summer of 2018.

Now, on a literal basis, this campaign was not about selling puts in order to buy stock at a big discount.

It was about selling puts for income - and then managing and repairing a trade that went against me when the stock traded (a lot) lower so that I still ended up booking damn good returns at the end of the day.

The ability to make good returns on bad trades is what I love more than anything else about selling puts - which we'll look at more in Chapter 6.

But the same "campaign" principle would've applied had my goal been to acquire AN at a steep discount.

- LEG #1 - The first leg of the campaign - in which I sold or wrote a single AutoNation MARCH 16 2018 PUT at the $52.50 STRIKE PRICE - brought in $157.28 in premium after commissions

- LEG #2 - On March 16th, I rolled the $52.50 short put out one month to the APRIL 20 2018 Expiration Date for a $0.94/contract net credit, or $85.50 in additional net premium after commissions (i.e. with the stock trading @ $50.67/share, I paid $1.86/contract to buy back my expiring MARCH $52.50 short put but collected $2.80/contract for selling the new APRIL $52.50 put)

- LEG #3 - AN continued trading lower, and on April 2nd, with the stock down to $45.48/share, I rolled and adjusted the position for a smaller $23.77 net credit (I bought back my APRIL 20 2018 $52.50 SHORT PUT for $7.10/contract and then sold TWO MAY 18 2018 PUTS at the $48 STRIKE for $3.80/contract, or $760 total before commissions)

- LEG #4 - On May 18th, with the stock trading a little higher ($46.39/share), I conducted another straight roll out one month, to the JUNE 15 2018 expiration date, for another $121.97 in new net premium, or $0.66/contract net credit times 2 contracts (buying back the MAY $48 PUTS for $1.66/contract and selling TWO JUNE 15 2018 $48 PUTS @ $2.32/contract)

- LEG #5 - The final leg of the campaign involved one more roll/adjustment on June 13th when the stock had rebounded some to $48.40 - this time I rolled the position out one more month and reduced the contracts from two back down to one and still collected a $61.73 overall net credit on the new leg (buying back TWO JUNE $48 PUTS @ $0.35/contract and selling a single JULY 20 2018 $48 PUT for $1.46/contract and then, one day before expiration, with the stock trading @ $49.41/share, I exited the trade by buying back the JULY $48 SHORT PUT for $0.05/contract)

Whew!

Those are a LOT of numbers, I know.

Here's the important takeaway:

By conducting rolls and adjustments, I was able to collect and book an accumulated $450.25 in total premium - meaning my theoretical cost basis (assuming assignment at the $48 final leg strike price) would've been all the way down to $43.50/share.

Now that's a freaking discount!

Smarter Ways to Buy Stock at a Discount When Selling Puts

But if you keep rolling and adjusting and managing an in the money position until it's out of the money and you're no longer at risk of assignment, how do you ever acquire your shares at the big discount?

Because, as you can see, at the time I exited the trade, the position was comfortably out of the money (the $49.41/share price of the stock was well above the $48 short put strike price one day before that put was set to expire).

Again, the purpose of this trade was for the income, not the stock discount.

Had I really wanted to acquire AN stock at a serious discount, I had multiple ways of doing that:

Technique #1 - Allow Assignment

At any point when the short put position was in the money (i.e. the share price trading below the put's strike price), I could've allowed assignment at expiration by NOT rolling or adjusting.

But isn't that falling into the same trap I referenced earlier, namely that the "discount" comes mostly from the falling share price?

Not necessarily.

It depends on how much total net premium I've collected and how much in the money the position is when allowing assignment.

If I had brought in $450 of total net premium over the life of the campaign and the stock was trading just a shade under the $48 strike price at the final expiration, then that really is a significant discount.

Remember, in theory, you can keep this process going for as long as you like.

And the more net premium you accumulate over time, the bigger your adjusted cost basis discount will be when you do allow assignment.

Practically speaking, however, there are reasons why you wouldn't want to keep the process going indefinitely.

If the stock began trending higher, I wouldn't recommend chasing the stock by rolling your short put(s) out and up to higher strikes, which could cause your breakeven/cost basis to actually move higher, not lower.

Technique #2 - Buy Shares on the Open Market

Who says you have to be assigned in order to buy a stock at a major discount?

A far more effective technique - and one that puts you in the driver's seat - is to manage your trades so that you don't get assigned, and then at the point of your choosing, make your own open market purchase of the stock.

At the time I exited the AN trade, the stock was trading @ $49.41/share, and there was nothing to stop me from simply buying 100 shares on the open market for $4941.00 before commissions.

Factoring in the $450.25 of accumulated net premium, that would give me an effective cost basis of $44.91, or a $4.50/share (or 9.11%) discount to the then current share price.

And if you want to get even more creative, who says you have to buy 100 shares? It's an open market purchase, so you can buy however many shares you want.

For example, what if I had chosen to buy 50 shares on the open market upon exiting my short put trade?

>> Before commissions, 50 shares of AN times $49.41/share = a $2470.50 open market purchase price.

>> Factoring in or deducting my $450.25 of accumulated net premium brings my net purchase price down to $2020.25, or about $40.41/share, or a $9/share (or 18.23%) discount to the current share price!

Technique #3 - Pausing a Campaign

Here's something else to think about.

Who says your put selling campaign to buy stock at a big discount has to be uninterrupted?

If you're selling puts on the stock you want to acquire for a big discount, and that stock is already trading in value territory, and then suddenly it's not, you can simply pause your campaign.

As I mentioned earlier, in my view it's not a good idea to chase a stock higher by selling puts at higher and higher strike prices (especially if you want to buy that stock at a discount).

If or when the stock pulls back again, then it's simply a matter of resuming that campaign by selling new puts on the stock.

Here's a good - if extreme - example:

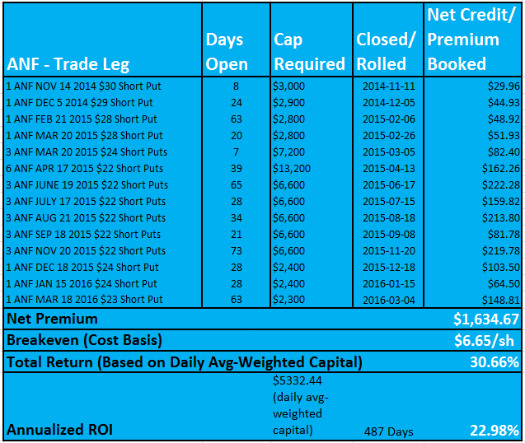

Back in the 2014-2016 period I had a very long running short put trade on ANF (Abercrombie & Fitch).

Again, as with the AN trade, this was about selling puts for income not discounts, but the same principles apply.

The campaign ended up being a 487 day trade that netted me 30.66% total returns (or 22.98% on an annualized basis):

Same story as with the AutoNation short put campaign - each roll or adjustment involved collecting a net credit, or receiving more for selling the new put(s) than what it cost me to buy back or close the previous put(s).

And aggressively working the strike price lower in the process as the stock traded lower over time.

The returns on this "bad" trade were so good, I would've happily kept the trade going forever.

But eventually the stock made a big move higher and when I let the position go, the stock was trading above $32/share.

But guess what?

By 2018-05-26, ANF had tumbled again and was trading @ $20.89/share - at which point I sold a brand new ANF AUG 19 2016 $20 PUT.

That brought in another $129.50 of premium after commissions. The stock closed at expiration trading @ $22.55 and I allowed my $20 short put to expire worthless.

Now, I didn't include this leg in the main trade campaign table above, but I certainly could have - and that would've lowered my potential cost basis even more.

My point here is that if you're going to apply the proceeds of a put selling campaing to the eventual open market purchase of a specific stock, there's no rule that says your campaign can't take a break from selling puts on that stock when it makes sense to do so.

Technique #4 - Think in Terms of Your Overall Portfolio

Finally, after you've transitioned from a single trade mindset to a campaign mindset, there's one more profound mind shift available to you if you're serious about buying stocks at the biggest discounts possible.

And that's when you make the shift from specific campaign to viewing your entire portfolio as a discounting and funding machine.

What exactly does that mean, and how does it help?

Well, let's go back to our insurance company analogy.

Insurance companies have a pretty sweet deal.

They take in premium upfront, hold on to massive amounts of cash and then only later, pay out a portion of that premium in the form of claims.

In the meantime, all that cash they hold (called the "float") is investible.

Most insurance companies invest their float in fixed income, so in higher interest rate environments, these companies can earn more from their investments than from their own operational earnings.

Warren Buffett took this model to another level with Berkshire-Hathaway.

In the early days, Berkshire had a heavy concentration of insurance operations (and obviously still does a lot of insurance business).

But instead of parking the float and operational earnings into fixed income, Buffett plowed the money into attractively priced, high quality, and high cash flow businesses and their stocks.

And that gave him both income in the form of dividends along with the potential for a great deal of capital appreciation (which, of course, is exactly how things played out.)

Buffett's success has come from his ability to reinvest, on a large scale, high cash flow opportunities into additional high cash flow opportunities.

The perfect recipe for creating the world's largest snowball.

(Source: Guinness World Records)

My premise is that you and I can do the same thing.

We can sell puts to achieve the same results - generating high cash flow from multiple low-risk, insurance-like option trades and then reinvesting those proceeds into shares of attractively priced high quality companies.

And not just the stocks we sold our puts on.

Example - Let's say your put selling operations are bringing in $1000 a month of income from multiple trades.

You can accumulate those funds and then re-invest them all at once into the open market purchase price of your favorite high quality stock when that stock is trading at an attractive valuation.

Even if you never sold a put on that stock.

So maybe after four months, you buy 100 shares of your favorite stock for $40/share - but because the funds to purchase those shares came from the proceeds of your various option selling trades from the previous four months, your cost basis on the shares would essentially be zero.

Or maybe you buy 200 shares and settle for a 50% discount on the stock.

There are two reasons why using the proceeds of put selling on Stock A to acquire shares of Stock B really is worth considering:

- It allows you to concentrate the power of your full portfolio into the acquisition of one stock at a time and thereby manufacture much larger discounts

- It's also crucial to recognize that a great investment may not make a great put selling trade

Just because a high quality stock makes a terrific long term investment, that doesn't mean it's always going to make a good put selling trade.

The stock's options may have low implied volatility levels, or they may be thinly traded, or the underlying nominal share price may be too high, or any other number of reasons.

And one of the hallmarks of our trading approach inside the Leveraged Investing Club, we start our short put trades with relatively small position sizes - whether we're selling puts for income or in order to buy stock at a discount.

- For the income route, small position sizes are much easier to manage and repair (which we'll cover in Chapter 6).

- And for the discount route, we still never want to be assigned the shares against our will - because we want to buy shares on our terms, not Mr. Market's, and the longer we're in a trade, the lower we work our cost basis.

Bottom line - trade management and trade repair is just as important if you selling puts to buy stock at a discount as it is if you're selling puts primarily to generate current high yield income.

Does Warren Buffett Sell Put Options?

Most investors don't realize this, but Warren Buffett has, through Berkshire-Hathaway, sold puts in a very big way - and both to buy stock at a discount as well as to generate investible income.

Check out this GuruFocus article for the full details, but the short version is that:

- Buffett and Berkshire sold 50,000 out of the money put contracts on Coca-Cola back in 1993 (collecting $7.5 million in premium)

- He also sold around 55,000 puts on the Burlington Northern Santa Fe railroad in 2008 before Berkshire eventually acquired the entire company

- And during the Financial Crisis of 2008-2009, he sold special equity index puts against the S&P 500, the FTSE 100, the Euro Stoxx 50, and the Nikkei 225 with expiration dates ranging from September 2019 through January 2028

Buffett's large short put trades on Coca-Cola (KO) and Burlington Northern (I think the stock ticker back then was BNI) was about buying shares at a discount.

The puts he subsequently sold on the four major indexes in the U.S. the U.K., Europe, and Japan are fascinating case studies in creative financing.

From selling these special puts (the counterparty wasn't other traders or market makers but rather some pretty big players such as Goldman Sachs), Berkshire-Hathaway collected $4.9 billion in premium which Buffett then reinvested.

I consider this a form of selling puts for income even though Buffett reinvested the proceeds - but sometimes the line between selling puts for income and selling puts to buy stock at a discount can blur.

Selling Puts to Buy Stock at a Discount - Conclusion

Small, one time discounts are better than nothing, of course, but the takeaway here is that you can do much better than that.

I used to do a Secret Seminar occasionally on a very simple, mechanical approach to manufacturing your own "Sweetheart Deals" on your favorite stocks.

It included a video and report.

I now offer that report for free on this page.

It's a good introduction to what's possible for long term investors with a more substantive understanding of writing or selling puts.

It's not exactly what we do inside The Leveraged Investing Club, but it's exponentially superior to the superficial way the strategy is almost always explained and employed.

My point is this: You don't have to settle for small, one time discounts, and you don't have to settle for the "wisdom" of the herd.

Once you free yourself from the oversimplified, generic descriptions of put selling, you begin to understand the incredible flexibility and potential of the strategy.

Chapter 3 - The Best Stocks for Selling Puts

We're going to look at specific set up criteria to use when looking for great put selling trades in Chapter 4.

But before we get to that, we need to step back and consider - in general terms - the kind of stocks that are best suited for selling puts on.

Said another way, this chapter is about the best stocks at a structural level for selling puts, and Chapter 4 is about the best conditions for timing your trade entries.

And we'll break down our exploration of the best put selling stocks into the following categories:

- Logistical Requirements for Selling Puts

- Sufficient Premium

- High Quality Businesses vs. Profitable Businesses

- Selling Puts on Value Stocks vs. Selling Puts on Growth Stocks

#1 - Logistical Requirements for Selling Puts

Not all stocks are optionable (i.e. have options that you can trade), and not all optionable stocks are suitable for selling puts.

In fact, it might be more helpful to identify the factors and components that exclude a stock from being a good trading candidate.

Not only will that help clarify what does, in fact, make a suitable potential candidate, it underscores an important point I've come to believe:

When the conditions are right, and assuming you follow some important set up criteria, the pool of potential trade ideas is very large indeed and there is no shortage of good trades out there.

Yes and no.

Beginning mid-year 2018, inside the Leveraged Investing Club, we also began incorporating small, conservative bear call spreads on stocks we felt were unlikely trade higher in the near term.

We'll have a lot more to say about Limited Downside Situations for selling puts in Chapter 4, but you'll have maximum flexibility if you can also flip the switch as it were and benefit from stocks that are in the process of topping out and turning over (by selling calls) vs. only benefiting from stocks that are bottoming out and rebounding (by selling puts).

We try to enter one new trade a week (with initial target durations that are generally in the 3 week to 45 day range, although when the trade really works out, we'll often be able to exit way ahead of schedule and lock in most of the trade's max potential gains in an abbreviated holding period) - but we now go with whatever the best set up is.

Some weeks that's going to be selling a put.

Other weeks, that's going to be setting up a small, conservative bear call spread.

My point is that finding great trade ideas - whether you sell both puts and calls as conditions warrant, or whether you only sell puts - is rarely an issue.

Yes, you really can still find attractive put selling trades even in a bear market (more on that in Chapter 6).

Types of Stocks to Avoid Selling Puts On

At the most basic level, you want to avoid selling puts on any stock where the options are structurally unattractive.

What I mean by that is a situation where the options in question don't provide very good choices or terms.

This is almost always a result of the options themselves being thinly traded - that's the common denominator.

When that's the case, you'll frequently find any or all of these less than ideal components:

- Strikes Priced in Wide Increments

- Wide Bid-Ask Quotes

- Limited Number of Expiration Cycles

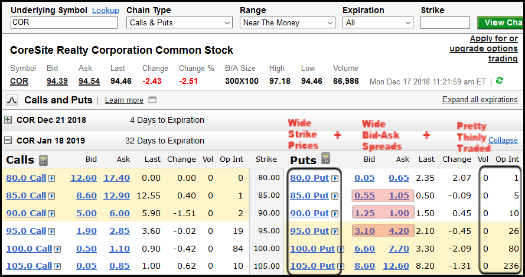

Let's look at an example - simply at a structural level - that would be a bad stock to sell puts on:

You can see it for yourself - the strikes are priced in $5/increments, the bid-ask spreads are ridiculously wide, and there's very little option trading volume.

What that means is poor and inefficient pricing for option traders.

True, you should always submit your option orders as limit orders, and unless the bid-ask spreads are particularly tight, try to get better pricing the quoted prices.

But when you see really wide prices like this, it's going to be challenging to get a decent price.

And once you're in a trade, you're totally at the mercy of the market makers if you want to exit a successful trade early or roll or adjust an existing position.

The big $5/contract increments between the strikes can also be a problem. The fewer strike prices that are available, the less precise you can be setting up your trades.

And finally, although you can't tell from the option chain above, in our COR example here, there are a very limited number of expiration cycles available - in this case, the December 2018 monthly options expiring in only a few days, January 2019, February 2019, and May 2019.

And that's it.

That may not be an issue when setting up your trade, but it can be an issue during the trade management process if you need to roll your position (we'll cover put selling trade management in Chapter 6).

Now, I don't advocate rolling a position ridiculously far out in time, but again, as with the limited number of strike prices, the fewer choices you have, the less flexibility and efficiency you'll have managing your trades.

Best Stocks for Selling Puts

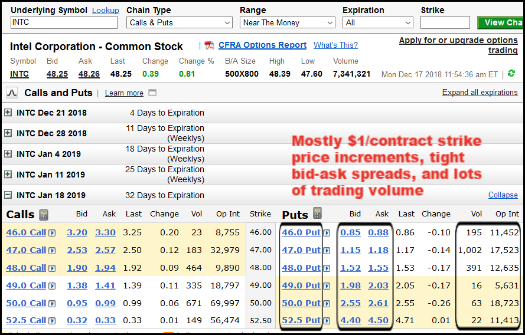

In contrast, let's look at an example of a stock with the complete opposite characteristics:

As you can see here with INTC (which we've traded on multiple occasions inside the Leveraged Investing Club), this is a very trading friendly security:

- The strikes on the monthlies are priced in nice, friendly $1/increments (the weeklies are even better as they're price in $0.50/contract increments)

- the bid-ask spreads are very tight

- And as you can see, INTC options get traded a lot

- Finally, what you can't necessarily see is that, in addition to trading weekly options, INTC options include expirations that go out for 2+ years

Put all that together and it spells a structurally favorable stock on which to sell puts - when specific set up conditions warrant, of course (which is what we're going to discuss next).

#2 - Sufficient Premium

When selling puts, it's a lot like the story of Goldilocks and the Three Bears.

If you sell puts with super high premium levels, that's a good indication that you've entered a high risk trade.

But you don't want to sell puts where the implied volatility pricing is too low because that can also be risky in its own way.

That's because the premium you collect upfront has a direct impact on how much of a downside buffer your trade initially has.

The more premium you receive when selling a put, the lower your initial breakeven or cost basis will be.

And it can also be more challenging to manage or repair trades with lower implied volatility levels for the same reason - there's not enough new time value available for effective rolls and adjustments.

(Don't worry - we'll cover these concepts in more detail in Chapter 6.)

Calculating Implied Volatility

The premium available when selling an option is a direct result of how volatile Mr. Market expects the underlying stock to trade during the life of the option in question.

You can usually find an option's implied volatility figure - represented as an annualized percentage move in the underlying stock - on an expanded option chain.

The implied volatility figure tells you the annualized share price range of the underlying stock over the option's holding period.

Project Option has a really good article explaining implied volatility.

While I don't specifically use the implied volatility figure to set up or manage trades (I use the annualized return metric which I'll explain in a sec), I've found in general that selling options with implied volatility percentages in the mid-teens or lower is usually a deal breaker.

Conversely, when selling options with implied volatility levels in the 30s or higher, be aware that the underling stock is likely going to be moving around quite a bit.

A Better Way to Ensure You're Selling the Appropriate Amount of Time Value

I personally use the annualized metric when setting up a short put trade.

There are similarities with the implied volatility calculation, but I find the annualized figure is easier to work with (because I can calculate it myself) and it makes a lot of sense.

I basically take the premium available and calculate what my annualized returns would be on a cash-secured basis assuming the trade is held to expiration and that your short put expires worthless.

For me, I've found that targeting 15-25% annualized returns on new trades balances things out very nicely - it ensures I'm getting sufficient compensation for my put selling services while keeping me grounded and away from higher risk setups.

For more information on how and why to trade and manage trades with the annualized metric, check out this site article.

#3 - High Quality Businesses vs. Profitable Businesses

I use to be a real stickler for only selling puts on the highest quality businesses I could identify.

That was especially true during the Financial Crisis fallout and Great Recession. I only wanted to work with stocks where the underlying business could survive Armageddon, because that's nearly where we found ourselves.

And in the several years that followed, selling puts on high quality stocks was the gift that kept giving - implied volatility levels were very good even on world class consumer staple type companies.

But eventually those opportunities became less and less so that simply selling puts on stocks like KO and PG no longer paid that well except under very specific situations.

At the same time, our trade selection, management, and repair processes have become so much more effective (and efficient with our capital), and as I actually tested my biases in the real world, I found that when the valuation and technicals were on our side, all we really needed was a profitable business.

While we may not be able to pinpoint it ahead of time - there will ALWAYS be a point below which Mr. Market simply cannot push the stock of a profitable business any lower.

Bottom line - there's a limit to how low Mr. Market can sink the shares of a still profitable business, but there is no such limit to how low I can reduce the breakeven/cost basis on my trade

Again, we'll talk more about how to manage and, if necessary, repair put selling trades that move against you in Chapter 6.

But a good way to think of a "bad" put selling trade is that while Mr. Market can sprint faster than we can, we have much greater stamina and can cover more ground than he can over time.

There may be uncertainty as to how low a stock will go before finally bottoming (but even the most hated stocks of profitable businesses will eventually find a floor, and the returns on our "bad" trades aren't going to be anywhere near our "good" trades, but as long as we don't sabotage our trades, I firmly believe that never losing money in the stock market is a legitimate objective.

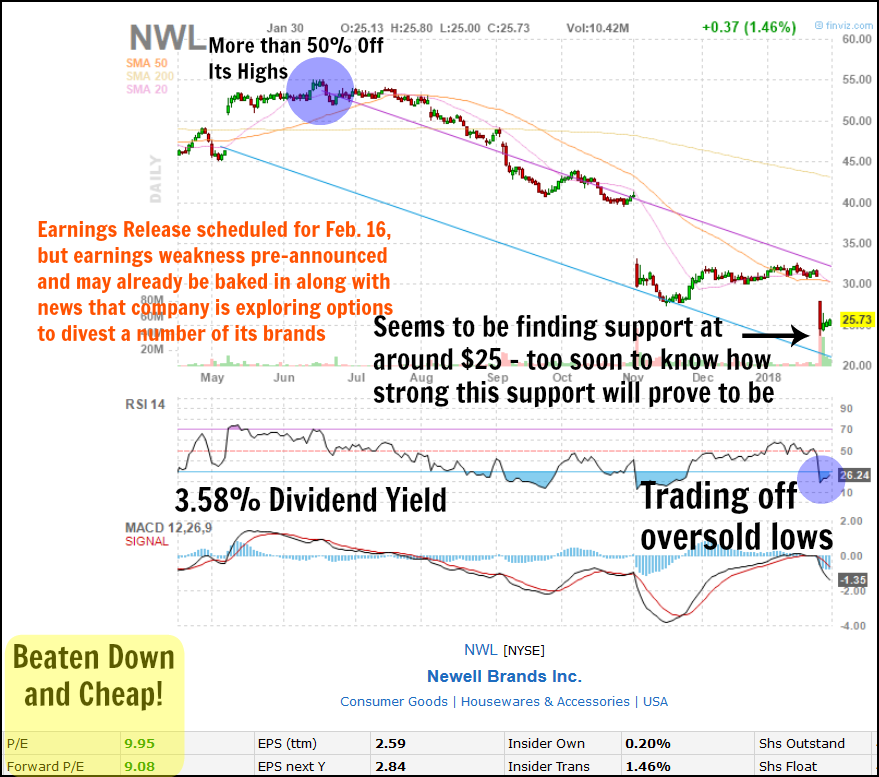

In 2018, for example, we successfully sold puts on a number of questionable, beaten down, or just plain hated stocks like DISH, NWL, HBI, DHI, and SIG.

At the end of the day, it goes back to what we covered in Chapter 2 - Selling Puts for Income vs. Selling Puts to Buy Stock at a Discount.

If your primary objective is to acquire heavily discounted shares, then definitely choose high quality stocks when selling puts.

But if you're selling puts as a way to generate safe, high yield income, as long as you approach your trades in smart and sensible ways, know that there can still be great - and still low risk - opportunities on stocks that would be considered lower quality.

#4 - Selling Puts on Value Stocks vs. Selling Puts on Growth Stocks

Is it better to be prepared for a natural disaster, or to avoid living in an area prone to experiencing them in the first place?

That's an important question - and it's also one that, in a weird way, put sellers have to ask themselves as well.

Not literally, of course.

But as a put seller, you do have to make a similar choice - are you going to sell puts on value oriented stocks, or are you going to sell puts on growth type stocks?

I realize it's an oversimplification to divide the entire stock market into value stocks and growth stocks.

So take what might be considered arbitrary classifications with a grain of salt.

We're painting with a broad brush here in order to identify the principles involved, in order to understand at the structural level the implications of the choices available to us.

Avoid the Bad Moon Rising

Don't go around tonight

Well, it's bound to take your life

There's a bad moon on the rise

- Creedence Clearwater Revival

I'll cut right to the chase - I'm with John Fogerty on this one.

I prefer to avoid trouble altogether in the first place if at all possible.

I avoid selling puts on richly valued stocks, no matter how attractive I think the fundamentals or technicals are.

If there are any hiccups along the way, the repricing of a stock can be sudden and severe. And with an elevated share price, it can be a long way down.

I'm not criticizing anyone who sells puts on momentum stocks, because you really can make some big returns over time if everything works out.

But I know what works for me, and what my ultimate objective is - to make money on every trade I enter and to NEVER lose money.

Heads I Win, Tails Mr. Market Loses.

If you understand how to exploit them to their fullest, short puts can be very flexible and forgiving - but the less carnage you expose yourself to, the better.

Short puts - in the right hands - can handle stormy seas. But that doesn't mean you should seek out hurricanes for sport.

Even before I developed and perfected the super effective 4 Stage Short Put Trade Repair Formula, I used to jokingly say about selling puts that the first 30% decline in the stock was manageable.

It was that second 30% decline where things started to hurt.

The craziest (because is was also very lucrative) naked put repair job I've ever done was the Legendary ANF Trade.

This is where the stock dropped 49.94% (at its closing low) after I entered the position (yikes - and the stock had already fallen a lot even before I sold my first put).

But when the dust settled, I actually made actual gains of 30.66% total or 22.98% annualized on real cash-secured capital over 487 days.

(Believe me, with those kinds of returns, I tried to keep this trade going for as long as possible.)

In contrast, the $SPX was actually down -0.88% during the same time period (early November 2014 through early March 2016).

It's OK to be Wrong, but Much Better to be Right

So while we can repair just about anything Mr. Market throws at us, it's still in our best interest to be as disciplined and as careful trying to be "right" as much as possible because the returns are going to be that much better.

And while it's a sensational feeling knowing you can be wrong on a trade and almost ALWAYS still come out ahead, the trades where you were right to begin with obviously require virtually zero maintenance.

Case in point - I mentioned above that ANF had already fallen a lot before I ever entered the trade.

As much as the stock would fall further after I sold my first put, missing that first big leg down was a big help.

Had I sold ANF puts at the top, it would've been a much tougher trade and far less lucrative.

Anytime you sell puts at what turns out to be a top, you make trade repair that much more difficult.

And for me, trade repair - i.e. never losing money on a trade - is my highest priority.

Doesn't mean I'm right or that that's the only approach, of course.

There's also a widely used approach to option trading built on the model of being willing to accept smaller losses (at least one hopes they're smaller) while gunning for and theoretically maximizing returns on winning trades.

Ultimately, our objective really is to never lose money in the stock market.

Period.

And that's much easier to do when we're wrong about a value investing situation than it is if we're wrong about a richly valued, high growth, priced for perfection, momentum type stock.

When looking for great trade ideas, our primary focus is on identifying what I call Limited Downside Situations.

Ideally, we want to identify MULTIPLE reasons why a stock is unlikely to trade lower, or lower by much, in the near term.

And valuation is a key component of our considerations.

So how was I so wrong about ANF's downside then?

LOL - There was a bit of a misunderstanding with the Legendary ANF Trade.

It was originally designed to be a very short duration trade - basically in and out before the upcoming earnings release at the end of the month.

Now, years later, I still maintain that was a good call and that I rightly identified a strong technical support level that was unlikely to be violated prior to that upcoming earnings release.

But what I HADN'T anticipated was that the quarter had been SO bad that the company felt compelled to issue an earnings warning in advance.

Crap.

Technical Support? What technical support?

The stock dropped like a rock and then Mr. Market and I were off to the races.

We'll Take After, Thank You Very Much

So we're much more interested in opportunities where the air has already been let out of a stock and there's no longer much downside remaining.

Another side benefit of working with out of favor stocks is that their options tend to have much higher levels of premium.

They're more expensive - so we get paid more for selling them.

Again, one of the saving graces of the Legendary ANF Trade was that those options had such high levels of implied volatility priced into them that the trade was easier to manage as a result, even as it was pretty underwater for a while.

We do consider factors other than valuation, and we also incorporate basic technicals to help us get the timing right on our actual trade entries.

The important thing is that with our "Limited Downside Situation" value investing oriented approach to selling puts, we don't need the stock to go up.

We just need it to not go down.

And that makes our task immensely easier.

Here's the beauty of the Sleep at Night Strategy.

When selling puts, we're not specifically looking for stocks that we believe will trade higher, and we're not specifically looking for stocks that we believe will trade flat.

We're just looking for stocks that aren't likely to trade lower.

When we're right - by definition - we're going to end up with a lot of stocks that do, in fact, trade higher.

That's the best outcome of all because a naked or short put will lose value most rapidly (which we want, of course) when the underlying stock trades higher).

When that happens, we're often able to lock in a majority of a trade's maximum potential profits in an abbreviated time period - and then we're free to go out and repeat the process.

A potential problem with growth or momentum stocks is that momentum works both ways.

So when a momentum stock stops trading higher, there's a good chance it's going to reverse course and head lower rather than simply trade flat.

Check out this 3 year chart on CMG (click to enlarge), which had been a Wall Street darling for years and routinely traded at 40+ times forward earnings:

The stock would trade even lower - down to around the $250/share level by the end of 2017 and beginning of 2018. From around $750/share to around $250/share over roughly 2-1/2 years.

That's more than a double whammy - that's a double body blow:

- The stock loses two-thirds of its value

- It takes an insane 2-1/2 years to finally bottom

How long it takes a stock to bottom on those trades where we're wrong is critically important to the naked put repair process.

The longer the bottoming process takes, the longer you're going to be in a trade, of course, but the lower your final returns will also likely be on an annualized basis.

With the Legendary ANF Trade, for example, the trade was technically repaired within about 7 months (with somewhere around a 17% annualized ROI).

I chose to keep the trade going after then - and until the share price finally started moving higher again - in order to rack up the returns. The "post repair" part of the trade was producing annualized returns around 28%.

The Case for Selling Puts on Growth or Momentum Stocks

OK - all of the above is true, of course, but it's also arguably pretty one sided.

Yes, you're susceptible to experiencing some severe pain if you sell puts on a high growth stock at what ends up being a multi year high and then the bottom falls out of the stock.

But what makes a growth stock in the first place?

It's very simple - growth.

A stock that keeps trading higher and higher and higher. A stock that Mr. Market is in love with. A stock that value investors complain about year after year after year for being too expensive - and still the stock keeps powering higher.

As long as the premium levels are high, you can make a lot of money selling puts - and chasing higher - a stock that trends higher over a multi year run.

That CMG example?

From around $50/share to around $750/share by mid-2015, the CMG share price rose about 1400% with only one serious correction in 2012.

You don't get much easier money than selling puts on a stock like that.

So What's the Answer?

Like many aspects of option trading, at the end of the day, it comes down to being a personal choice.

As I've already explained, I sell puts from a value investing perspective rather than a momentum or growth stock perspective.

That's because my personal objective really is to never lose money on a naked put trade.

Seriously.

My concern then if I'm writing or selling puts on a momentum stock on what turns out to be the top is that my bag of tricks may not be sufficient to repair the situation.

Especially if, like with the CMG example, the underlying stock is going to shed two-thirds of its value, and take 2+ years doing it.

But you may not feel the same way.

You may feel the upside on stowing away via put selling onto a stock that rockets higher over a multi-year period is well worth the risk of that gravy train eventually coming to an end someday.

(And apologies for the atrociously mixed metaphor.)

If that's the case, the most important question is what can you do to limit or control the risks?

If you're going to live in tornado alley, or in a flood plain, or on the San Andreas fault, what can you do to better ensure your survival if or when that day of reckoning ever comes?

How to Make Selling Puts on Growth Stocks Safer

So if you're going to trade more aggressively by selling puts on growth or momentum stocks, how can you make that process just a little bit safe?

Just about any option strategy can be made to be more risky or less risky, and this is the case for put selling as well.

There are a number of factors to consider:

>> Small Position Sizes

Inside the Leveraged Investing Club, we initiate new option selling trades as "relatively small position sizes" (relative to the size of one's own account, or roughly one contract per trade on $50K accounts or smaller, somewhere around 8-12% of one's portfolio on larger accounts).

The same principle applies to selling puts on growth type stocks.

Yes, you're going to give up potential returns by scaling back the size of your trades, but you're also going to limit the damage Mr. Market can inflict on you if his feelings for the momentum stock in question ever sours.

This is also not a linear consideration.

If you've been successfully selling puts on a growth stock for a while, your capital - and capital requirements - have likely been increasing as well.

In other words, the amount of capital you have at risk is very likely to grow over time so that if/when the stock reverses course, the amount you have to lose has also compounded to a much higher figure than when you first started out.

>> Use the Bull Put Spread Structure

I tend not to set up very many bull put spreads and instead opt to simply go the naked put route.

It's important to recognize that there are two - very different, even mutually exclusive - purposes to setting up a bull put spread vs. a naked put (whether cash-secured or on margin):

- Leverage (bull puts require MUCH smaller capital amounts than do standalone short puts)

- Safety (adding an offsetting long put at a lower strike to your short put caps the maximum loss you can incur on your short put)

This is very important - you have to choose which way you're going to use credit spreads (whether bull puts or bear calls, which is the equivalent trade on a stock you expect to trade flat or lower).

Because you can't have it both ways.

You can't crank up your potential gains AND reduce your risks, and anyone who tells you otherwise either doesn't know what they're talking about, or, more likely, has an expensive credit spread service they're trying to sell you.

Red Flag Warning!

Look for those promoting a credit spread service to talk about return potential in terms of percentage, and losses in terms of total dollar amount per contract.

That's a very good indication that they do, in fact, recognize the risks of overleveraging credit spreads, but that they don't want you to.

What they say may be factually correct, but still extremely misleading.

The only way you get monster gains at a significant level is to expose larger portions of your portfolio to the very real risk of heavy, losses.

That's because credit spreads that cannot be converted back into their naked counterpart - because you traded too many contracts to do so - simply cannot be repaired in the same way that a naked option can.

If you think you're gong to get rich trading credit spreads - and that you'll be able to do so in a low risk manner - I would encourage you to check out this 4 part series on the pros and cons of credit spreads.

>> Incorporate Technical Analysis

Anytime you're selling puts for income rather than stock acquisition, I think you definitely need to incorporate at least basic technical analysis.

And that's true whether we're talking about being able to identify as early as possible when a growth stock's long term trend has broken down, or simply about improving the timing of trade entries, rolls, adjustments, exits, etc. in the near term.

And the good news is that, in my experience, you really don't need much more than basic technical analysis when selling puts.

>> Cutting Losses!

Yikes - it almost physically hurts to be typing this.

As my goal is to consistently make 15-25% a year selling options with virtually no individual trade losses (and in any and all market environments) the idea of willingly locking in a loss is, as they say, anathema.

But if you're going to be a put seller on growth and momentum stocks, losses are going to come with the territory.

You just want to make those inevitable losses as limited in scope as possible.

Are these losses really losses, though?

Because if you think about it, considering the larger picture and the total amount you've hopefully already booked when the party finally ends, you're not really booking a loss.

It's more like you're giving back some of the gains at the end of the night to help your host pay to clean up the place.

But in order to keep that final expense as small as possible, you have to be psychologically prepared for the end of the party and guard against denial.

You don't want to make the classic investing mistake that you sometimes see inexperienced investors make after a big run up in their stock.

The stock tops out, turns over, and then sells off. But instead of locking in their gains, the inexperienced investor holds on, thinking (and then wishing) the stock will "come back."

Often they end up losing money on what should have been (and once was) a big score.

Don't do that!

To Summarize . . .

As a put seller you have a choice to make - are you going to sell puts on value type stocks or on growth type stocks.

>> I personally find value oriented stocks a whole lot safer to insure than growth or momentum stocks (and when you sell puts, you're essentially insuring a stock).

>> There is a case for selling puts on growth stocks, however - the potential for much higher returns and under super easy conditions for as long as a stock's uptrend remains unbroken.

>> Finally, if you do choose to sell puts on a growth or momentum stock, I think you would be wise to consider setting up and managing your trades in ways designed to scale back some of the inherent risk - those include:

- Small position sizes

- Using a bull put spread structure (sensibly)

- Incorporating technical analysis

- A willingness to cut your losses (vs. automatically standing your ground and attempting to repair a trade if it goes south on you)

Chapter 4 - How to Find Great Put Selling Trade Ideas

In Chapter 3, we looked at the type of stocks that are appropriate for selling puts (and the type of stocks that aren't).

In this chapter we're going to look at the specific conditions that represent attractive setups.

This is exciting stuff because I'm not going to hold anything back here.

In this chapter, I'm going to show you precisely how I go about finding great put selling trades.

The Trifecta of Great Put Selling Trades

I periodically do a Secret Seminar series on the Trifecta of Great Put Selling Trades, or what goes in to finding great put selling trades.

Whether I'm selling puts for income or to buy a great business at a great price, I'm on the lookout for what I call Limited Downside Situations.

Limited Downside Situation: Ideally identifying multiple reasons why a stock is unlikely to trade lower, or lower by much, in the near term.

There can be any number of special situation factors that we can consider, but if I had to boil things down to their essence, there are three primary factors that make up the Sleep at Night Strategy (my highly customized put selling strategy) selection process:

>> Quality/Fundamentals

>> Valuation

>> Technicals

#1 - Let's Drill Down! (Quality/Fundamentals)

We touched on this in Chapter 3, but in a perfect world, we could just sell puts on KO, MCD, JNJ, and PG all day and get paid handsomely.

But quality on its own isn't enough.

The stocks of great businesses can become overvalued, and ugly technicals should scare you away from selling puts no matter how fantastic the underlying business is.

Interestingly, as the trade management and repair process I've developed (into what is now the highly efficient and effective 4 Stage Short Put Trade Repair Formula) has gotten better and better, I find that stringent quality standards are no longer required.

That is, as long as other crucial criteria are met.

In fact, I make the case in this site article that with our Sleep at Night approach, when we sell puts, it's less about insuring a stock at a certain price and more about insuring a stock against the ultimate risk - insolvency.

What that means in English, is that when we follow our other setup and management protocols, as long as the underlying business doesn't go bankrupt, we're probably going to be just fine.

So in terms of "quality" or the fundamentals, all we really require is confidence that the underlying business is going to remain profitable.

(As long as that happens, no matter how much Mr. Market hates on a stock, there's no way a stock will trade down to zero - and the 4 Stage Short Put Trade Repair Formula is so effective, that's the only assurance we need.)

#2 - Valuation - The Secret Safety Net

A few years ago, I really developed a much greater respect for the role that valuation plays in Limited Downside Situations.

Fundamentals and technicals tend to hog all the attention among traders and financial media alike, but I find that valuation can function as a secret but still very powerful safety net when it comes to selling puts.

I discovered this myself when selling puts here and there on stocks that would never be described as high quality - ANF, CAR, MS, UAL, KR, NWL, AN, HPE, MU, etc.

Not all these are bad companies in the least (the bullish case on MU, in particular, grew considerably a year or so later, but at the time it traded like it was in the doghouse. The common denominator on all of these was that I sold puts on these stocks when they were extremely cheap.

(MS and MU in particular were trading much, much lower back then.)

Again, continued profitability (even if those profits aren't terribly impressive) plus low valuation equals a powerful combination when selling puts.

But let's not forget the technicals.

#3 - The Dark Art of Basic Technical Analysis

Some caveats (and reassurances!) upfront as the subject of technical analysis can have some baggage associated with it:

- Nothing we do inside The Leveraged Investing Club involves hard core technical analysis

- I very much believe that technicals are NOT a crystal ball - they don't tell you what WILL happen but rather what's more likely to happen and what's less likely to happen

- We don't trade technicals in a vacuum, but it's often the first thing I look at because a bad technical setup is enough to immediately disqualify a trade

My Three Favorite "Technicals"

I also really believe in focusing on the "why" you're doing something or why something works.

That ensures that clarity is front and center.

So when it comes to selling puts inside the Leveraged Investing Club, our use of technical analysis is simply about answering the following questions:

- Where is the likely floor (or technical support) in a stock?

- Is the stock trading near that floor?

- Is the floor holding?

- Is it likely that the floor will continue holding?

Not all floors hold, of course, and even if a floor fails after you've entered a trade, it's not the end of the world.

(There will be other floors, and our trade management process allows us to, in effect, take the stairs and retrieve/rescue our trade that way.)

But the point is that we still want to be as disciplined as possible when first setting up a trade so that the technicals are on OUR side rather than on Mr. Market's.

(And if they're on neither side, we'll likely pass there as well since there are rarely a shortage of great ideas.)

As a reminder, this is all about identifying what we see as Limited Downside Situations.

And when it comes to the actual technicals, I'm basically just looking at three things:

>> Support and Resistance

>> The RSI (for identifying oversold conditions)

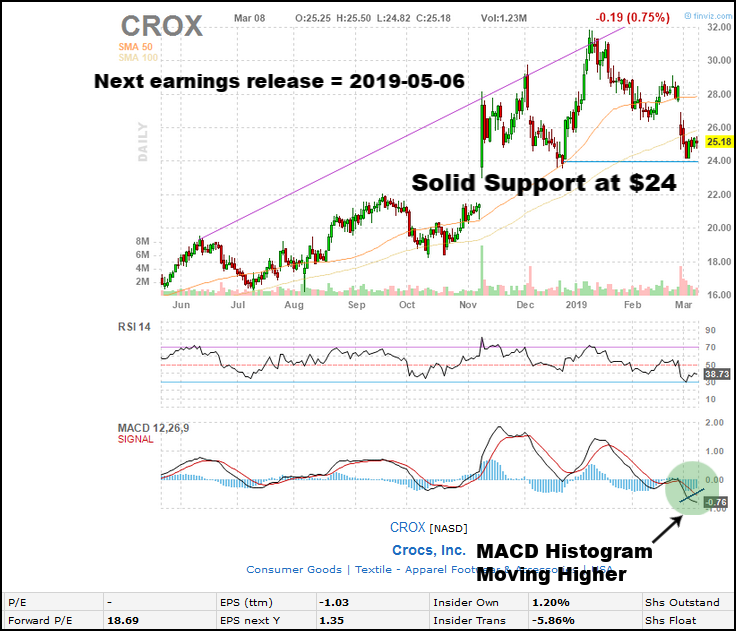

>> The MACD Histogram (for identifying successful tests of support + reversals)

Again, these three technical components are designed to answer our questions about the floor in a stock.

It's as simple and straightforward as that - no mysteriousness or mumbo-jumbo or other murkiness.

At its best - and most effective - technical analysis isn't about sorting through bird entrails in order to divine the future with eerie precision.

It's simply about holding our finger in the air to determine which way the wind is blowing.

So let's look at these one at a time . . .

#1 - SUPPORT AND RESISTANCE

This is the mainstay of technical analysis.

Support and resistance simply shows you - at a visual level - areas where a stock has previously found difficulty trading below (support) or above (resistance).

The assumption then is if these price levels proved problematic in the past, there's a good chance they're going to do so again in the future.

Another analogy that might be helpful is to think of support and resistance as checkpoints that a stock must pass through before continuing on its way.

Some checkpoints may be easier to get through, some may be more difficult, and some may simply be impossible at this point in time.

But once a level has been violated, it often serves as the opposite counterpart - meaning once a checkpoint as been passed through, it doesn't necessarily go away.

So old resistance, once overcome, can serve as a powerful new floor or support level, and vice versa.

If you're brand new to all this, Investopedia has a good introduction to support and resistance here.

(I'll go into more details - in the next issue? - of my two favorite charting websites - Finviz and StockCharts - both of which have free versions that you should be able to get by with.)

#2 - RSI (Relative Strength Indicator)

I love the RSI, which stands for Relative Strength Indicator.

It's an oscillator which measures momentum in a stock (either to the upside or to the downside) on a scale of 0 to 100.

Readings above 50 indicate increasing momentum or strength to the upside; below 50 indicate increasing downside momentum or weakness in the stock.

As you might expect, momentum traders find the RSI useful, but it has a secondary function that comes in very handy for option sellers.

Turns out that it's a great tool for identifying stocks that are technically oversold (readings below 30) or technically overbought (readings above 70).

Why is that important?

In general, extreme moves in a stock in the short term aren't sustainable over a longer period.

So when a stock makes an extreme move, it's similar to a rubber band being stretched to maximum capacity.

Something's got to give - and while a stock can trade flat for a while and resolve the oversold or overbought condition that way, it will often resolve the condition by reversing itself.

Either resolution is fine with us as put sellers.

If we're selling puts on an oversold stock, we really don't care if the stock trades flat or if it rebounds in some way. We just don't want it to trade lower.

(We do benefit more - or at least faster - if the underlying stock bounces since we're then able to exit the trade earlier and redeploy our capital ahead of schedule.)

This sounds interesting in theory, but it's much more powerful when you see it on a chart.

Just play around and check out the charts of random stocks on StockCharts or Finviz and you can see for yourself just how often an oversold condition corresponds to a near term bottom (or top) in the stock.

Oversold RSI readings on a stock can be a powerful tool in helping us find Limited Downside Situations.

I've also spent some time rummaging through the Leveraged Investing Club basement and found some charts from over the years where you can see examples of what I'm talking about.

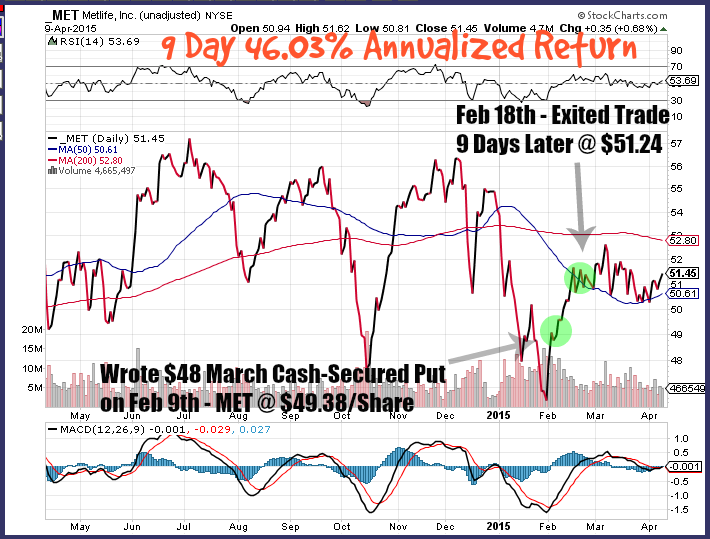

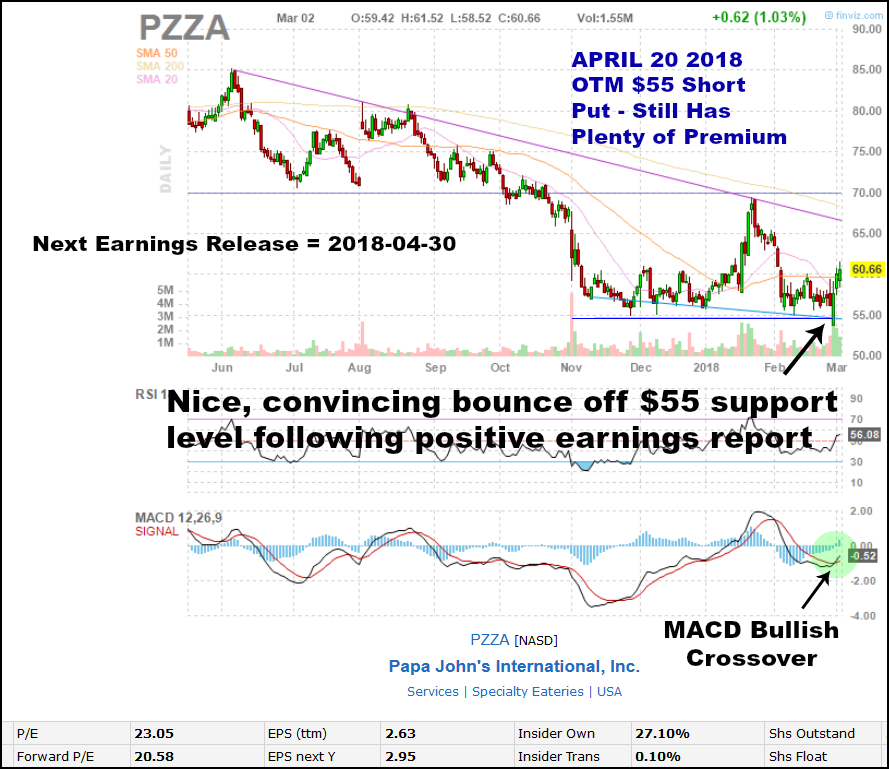

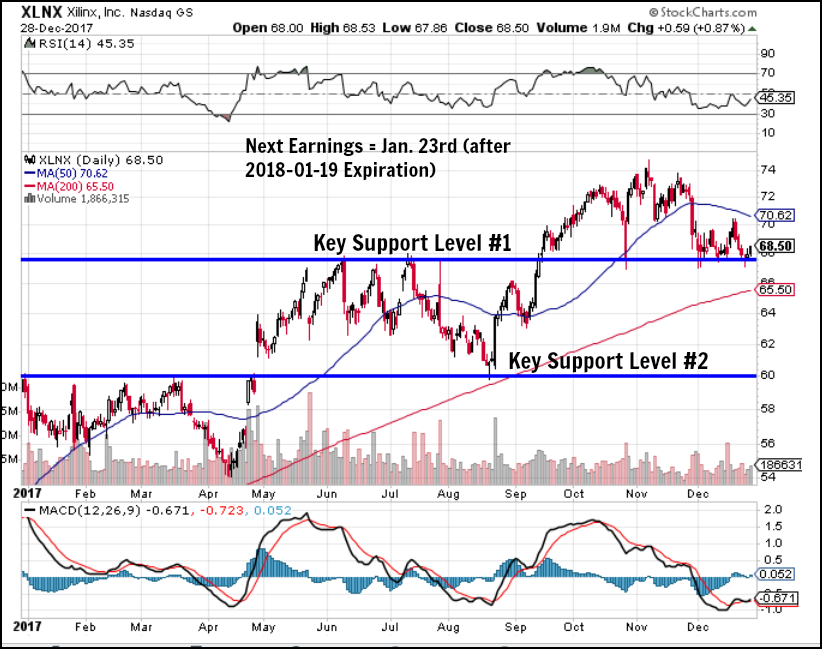

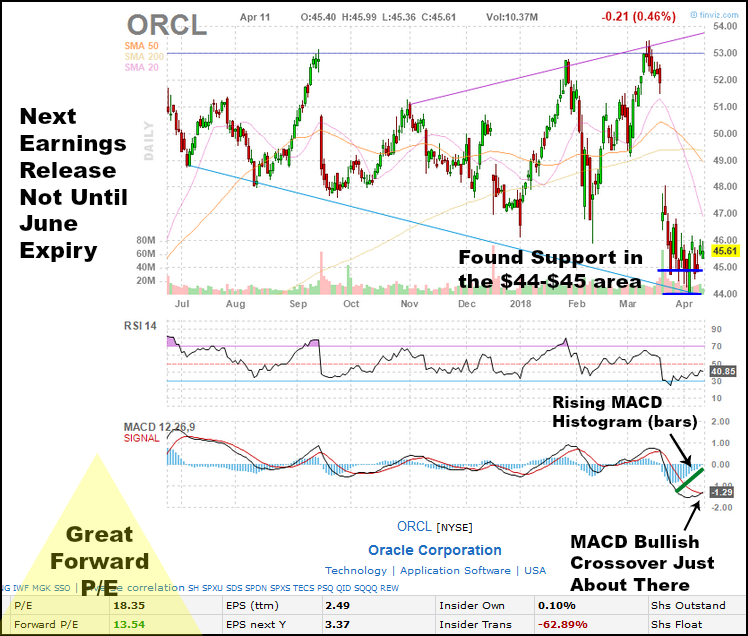

(These charts aren't specifically about the RSI, but I've added some commentary below so you can see exactly what I'm talking about):

MET - Multiple Oversold Readings

Check out the RSI reading at the top of the chart for October.

You can see that the RSI fell below 30 around mid October at the same time that MET registered a near term low.

And then over the next few weeks/months, the RSI fell to around 30 on multiple occasions which pretty consistently corresponded with other near term bottoms.

SIG - Oversold and Overbought Examples

This chart is great because it contains multiple examples RSI oversold and overbought readings - and you can see for yourself how consistently they corresponded with near term bottoms and near term tops.

- Both oversold/bottoms @ end of May/beginning of June

- A near oversold/bottom in late August

- An overbought/top in mid September

- And another overbought/top in November just before a huge sell off

Also check out the earlier oversold reading in mid May and note how the oversold condition resolved itself not by a big or definitive move higher, but by a move that was more or less sideways (right before the stock sold off again and registered an even more oversold RSI reading).

It's important to be aware that an oversold or overbought condition can be resolved that way (trading flat) as well as by a reversal in the share price.

TROW - Multiple Examples of Both Oversold and Overbought RSI Readings

Here's a two year chart with numerous examples of oversold and overbought RSI readings.

I'll let you identify these and see for yourself how often these extreme readings corresponded with a near term top or bottom in the share price.

If you've never used, incorporated, or considered the RSI this way before, I really encourage you to study these examples - and consider reviewing more on your own.

Again, I love the RSI!

It's a simple and cool and very powerful little tool.

It's not completely foolproof, of course, as an oversold or overbought condition can persist for an extended period under extreme conditions or circumstances.

Or said another way, just because a stock is oversold, that's not a guarantee that it won't continue being oversold or trading lower for longer than you expect/hope.

Again, technical analysis isn't a crystal ball - it's a weather vane.

So the function of the RSI (as we use in inside the Club) is to let you know when the rubber band becomes very stretched and therefore some kind of reversion to the mean is more likely than not.

And when you can combine it with a key support level, you've most likely got a very nice short put setup.

That's because, when selling puts, we don't need the stock to go up - we just need it to stop going down. And an oversold RSI reading goes a long way to helping us identify these opportunities.

(Or vice versa, of course, if you're dealing with a Limited Upside Situation and looking to sell calls/conservative bear call spreads against a technically overbought stock.)

But that leads us to the next big question - how do you know WHEN to pull the trigger and actually enter a trade?

#3 - MACD Histogram

This is definitely one of my favorite indicators and - as you might expect by now - I prefer simplicity over complexity.

And this one really is fairly simple (even if it may not sound like it at first).

So if support and resistance tells us where the checkpoints are, and the RSI tells us when a stock may have moved too far, too fast, the MACD Histogram is a surprisingly effective timing tool to let us know when a stock may be reversing itself.

Now the first important thing to note is that the MACD Histogram is not the same as the MACD (or Moving Average Convergence/Divergence Oscillator).

The MACD Histogram are the bars behind the MACD lines.

Here's a StockCharts article that provides more info, but basically what the bars do is measure the distance between the MACD and its signal line.

Err . . . . you guessed it - So What?!?

At the risk of seriously oversimplifying, when the MACD Histogram bars are moving higher (i.e. getting smaller when below the zero or midpoint line or getting bigger when above the zero or midpoint line), the stock's positive momentum is increasing.

Now, fair warning . . .