Constructing Multiple Lines of Defense Into Your Put Selling Trades

How to Safely Sell Options for High Yield Income in Any Market Environment

The biggest fear or objection to selling puts that some folks have is what happens in a big market sell off or crash?

In this comprehensive guide, we look at how to construct multiple lines of defense when selling puts so that you can continue generating safe, high yield option income in any market environment.

Defending Your Option Trading Castle

According to the UK website, Exploring Castles:

"Medieval castles were built to be as defensive as possible. Every element of their architecture was designed to make sure that the castle was as strong as it could be, and could hold out against sieges – which could sometimes last months."

These defenses included:

- The outer curtain wall

- Moats and water defenses

- Turrets and towers

- Machicolations (overhanging holes through which rocks, arrows, etc. could be used against attackers)

- Defensible gatehouse

- Drawbridge

- Barbican (additional defense for the gatehouse)

- The Keep (fortified tower or section of castle as a last line of defense)

And then you had multiple classes of soldiers from archers to the king's private guard and everyone in between.

Castles - designed to be amazingly effective at being defensible - are also a really good metaphor for what's possible for you and me when it comes to structuring our option selling trades.

Put simply, if we know what we're doing, we can design our trades to be just as impregnable.

If we do our part and run the kingdom with all our safeguards in place, we're going to be just fine and have a long and prosperous reign.

We just want to make sure we don't do anything to sabotage ourselves by not adhering to our protocols - like forgetting to close the castle gate or not having any arrows on hand for the archers.

A Brief History of Economic Moats

Warren Buffett has famously championed the concept of economic moats and made it the foundation of his approach to value investing.

Economic moats are basically structural and sustainable competitive advantages enjoyed by certain companies.

There are basically two approaches or schools of thought when it comes to value investing - price and quality.

There's what I call the Value Trading approach where the emphasis is on acquiring businesses or assets at a price that's materially below their true worth.

This approach doesn't consider the quality of the underlying business but simply asks whether you can acquire it for less than it's worth.

It can be compared to flipping a foreclosed or distressed home.

The other approach, which is arguably a more sophisticated form of Value Investing, focuses on the quality of the underlying business.

Ideally, you also want to pay as little as possible to acquire high quality assets, but with this approach, the primary focus is on quality, not solely price.

Warren Buffett's own evolution went from Value Trading to Value Investing (arguably out of necessity as Berkshire Hathaway grew larger and larger and now generates an insane amount of investible cash every year).

Hence Buffett's famous quote: "It's far better to buy a wonderful business at a fair price than it is to buy a fair business at a wonderful price."

Said another way, it's better to pay a fair price for a business with an economic moat (and a corresponding bright future) than it is to get a great deal on a kingdom existing on borrowed time.

More Than Just a Moat

When it comes to option selling, we want more than a single and simple moat, however.

We want the entire impregnable castle experience.

Our "Heads We Win, Tails Mr. Market Loses" approach isn't about jousting Mr. Market on a daily basis and defeating him head to head.

It's about consistently besting him because he simply can't get to us and ever lay a hand on us.

So we have a lot that goes into our trade selection and set up criteria.

Our entire approach is about constructing multiple layers of protection in every trade - from set up to management to repairs (if those become necessary).

Multiple Lines of Defense Spelled Out

So how does this analogy translate into the real world application of the (customized option selling) Sleep at Night High Yield Option Income Strategy?

Let's go through the multiple layers of protection - which are both at the trade AND the portfolio level - one by one.

- #1 - Opening Position Size

- #2 - Trading Both Sides of the Market

- #3 - Intelligent Diversification

- #4 - Never Selling Puts Remotely Near a Top

- #5 - Trade Management and Repair (using math, psychology, and the power of time value to handle anything Mr. Market throws at us)

Line of Defense #1 - Opening Position Size

Inside the Leveraged Investing Club, we start all our option selling trades as "relatively small positions."

We don't get too legalistic about having a precise formulaic definition of what that means, however.

Because if you have a smaller portfolio, until you can build up your capital, your initial position sizes are, by definition, going to be relatively larger than someone with more capital.

That's what "relative" means, after all.

This is also a good example of a principle being more important than a rule.

The Club's Insurance Company from Hell Portfolio is a $50K cash portfolio, and we tend to max out the number of open trades at somewhere around 8-12.

I've found that 8-12 max open trades provide more than enough diversification (and throughout this series, I'll have a lot more to say about what I consider to be "intelligent diversification").

On a $50K portfolio, what that means is that I typically initiate my put selling trades (or call selling trades in the form of small, conservative bear call spreads) with a single contract.

(If the underlying share price is nominally lower, say $25/share or less, then I might begin with two or three contracts.)

It's not the one contract that's important - it's the one contract in relation to a $50K portfolio.

So if I were officially running a $500K portfolio, I wouldn't be driving myself crazy looking for ten times the number of trades that I currently trade.

I would trade the same number of positions, but I would initiate those positions with a base of 10 contracts rather than one.

Why Relatively Small Position Sizes Matter

Spreading your trades - or investments for that matter - over a wider number of positions is just another way of describing the concept of diversification.

But the way financial media and the managed money industry treat diversification is that it's a way to limit the damage if/when a single trade or investment blows up on you.

That's not why we "diversify" at all.

For us, relatively small position sizes isn't about sacrificing the weakest of the herd.

It's about ensuring that every single trade is repairable if something goes wrong.

We have a very specific, customized, and deadly effective trade management and repair system that I personally developed (and fine tuned over the years, often through the school of hard knocks).

It's called the 4 Stage Short Put Trade Repair Formula (it also works on our short call based trades), which is only available inside the Leveraged Investing Club via the Sleep at Night High Yield Option Income Course.

We'll cover the trade management and trade repair more in depth later on in this article.

But one of the "stages" we sometimes (rarely actually) employ is that we'll add contracts to a trade if it really goes south on us.

It's based on what I call the Double Half Principle.

By doubling the number of contracts in an in the money position, you can effectively cut in half the distance between the current strike price of your position and the current underlying share price of the stock.

Huh?

Example:

If you sold/wrote a put on a stock at the $40 strike (essentially insuring or offering to buy it at that share price), and then the stock sells off and is now trading @ $30/share . . .

Your short put position is now $10/contract in the money.

Guess what else is also $10/contract in the money?

(2) $35 short puts.

In other words, if the underlying stock is trading @ $30/share, you can convert a single $40 short put into (2) $35 short puts.

Really think about the implications here - if you have unlimited capital and the stock in question doesn't trade down to zero, you should NEVER lose money selling puts.

Ever.

But Who Has Unlimited Capital?

I certainly don't, and I'm guessing neither do you.

And sometimes, when someone hears me lay out the Double Half Principle for the first time, they feel that the idea of adding more contracts to an already "losing" trade is a risky move.

After all, aren't you supposed to "cut your losers short?"

And "never throw good money after bad?"

"Unlimited Capital" Is an Illustration, Not a Requirement

I use the "unlimited capital" concept as a mathematical illustration.

Having huge amounts of capital held in reserve is simply not necessary.

In fact, to answer a very frequent question I get, I really don't hold any capital in reserve for future repairs - and as we work our way through this series, you'll see why.

Expanding an in the money (i.e. underwater) option selling trade is a powerful move, but one that we actually only rarely employ.

In fact, only about 5% of our trades inside the Leveraged Investing Club ever require additional capital.

And even then, it's usually not very much.

Here's a good example:

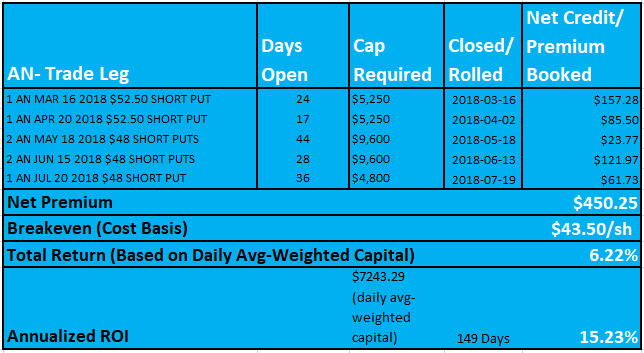

It was a 149 day put selling trade on AN (AutoNation) in 2018 that originated as a single $52.50 short put.

Unfortunately, the stock traded down into the mid-$40s.

Fortunately, we didn't panic or "cut our losses."

But at one point (the optimum time per our Trade Repair Formula), we added a second contract which enabled us to work the strike price from $52.50 all the way down to the $48 strike.

And for a net credit (it was small, of course, but we still received more for rolling/setting up the new position than what it cost us to close out the old/expiring one).

Eventually, the stock rebounded enough that we were able to exit the position - and for an overall 15.23% annualized return over those 149 days.

Some key points:

- Not only did we not lose money on this "losing" trade, we actually made damn good returns (and no accounting monkey business - this was all on real cash-secured capital)

- We didn't "need" the stock to ever come back to the original $52.50 strike - and, in fact, while it's come close a couple of times, as of early November 2019, the stock still hasn't retaken the $52.50 level!

- Expanding the trade reduced our risk - in this example, the concept is very clear - (2) contracts at the $48 strike was a lot less risky than (1) contract at the $52.50 strike (and it also made the trade much easier to manage)

It's Not About Unlimited Capital, It's About Not Overleveraging

I would argue that, with the AN trade for example, expanding the trade materially reduced the risk because it lowered the strike price (and the share price at which we could exit with all our accumulated net premium.

Now, no doubt about it, we also could have increased our risk if we overleveraged ourselves in the process.

And overleveraging in this process can take different forms:

- Larger initial position sizes

- Expanding a trade too soon

- Expanding a trade too often

Again, inside the Club, we employ this tool in only about 5% of all our trades - and even then, we're adding relatively small amounts of capital.

But - obviously - we don't know in advance what occasional trade will eventually need this kind of helping hand.

So we treat EVERY trade with the utmost of respect in case it's the one that we'll need to send the cavalry after.

And that includes initiating every trade as a "relatively small position."

Line of Defense #2 - Trading Both Sides of the Market

Now let's look at what I've come to see as one of the best ways to hedge your portfolio and set yourself up to succeed in any and every market environment.

One of the questions/concerns I routinely get - in one form or another - is what happens to put sellers in a bear market?

Now, I've made the case many times that you really can make good returns selling puts even in a bear market:

>> Not everything goes down in a bear market

>> Not everything that does go down in a bear market goes straight down

>> Premium levels spike (which means we can set up our trades more conservatively and STILL get paid very well)

But who says option sellers can (or even should) only sell puts?

Inside the Club, since May of 2018, we've also been selling calls (in the form of small, conservative bear call spreads).

And it was one of the smartest decisions I ever made.

Limited Downside Situations vs. Limited Upside Situations

So we've consistently had success selling puts (i.e. insuring or offering to by a specific stock at a specific price within a specific time frame) over the years on what I call Limited Downside Situations.

Or when we can identify multiple reasons why a stock is unlikely to trade lower, or lower by much, in the near term.

And what are these "multiple reasons?"

It basically comes down to fundamentals, valuation, and technicals.

(I lay everything out in detail in Chapter 4 of my Complete Guide to Selling Puts.)

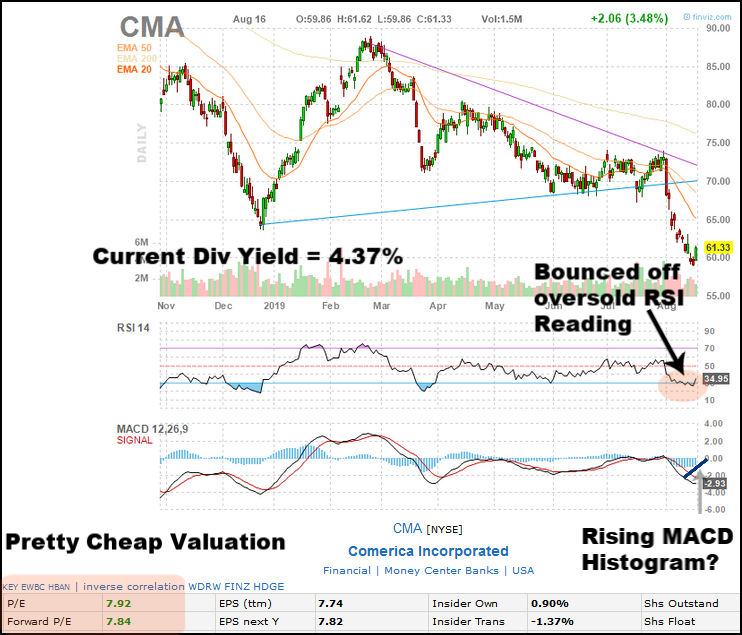

Here's a 2019 example of a short put trade we were confident to trade on CMA (when interest rates were plummeting, financials were in the dog house, and all the talking heads warned investors to stay away from this sector):

On 2019-08-19, with CMA trading @ $62.43/share, I sold a single CMA SEPT 20 2019 $60 PUT for $1.33/contract.

The stock closed at expiration @ $65.97/share, and the position easily expired worthless.

Our final returns were 25.07% annualized (on real cash-secured capital) over 32 days.

Flip the Put Selling Criteria for Limited UPSIDE Situations?

What I was unsure of was whether the same criteria we'd been using so successfully to sell puts on Limited Downside Situations could be flipped.

Could we sell calls (in the form of small, conservative bear call spreads) on Limited Upside Situations with, in effect, the opposite criteria?

I first tested this out in my personal account for 6+ months and was pleasantly surprised at how effective it was.

So much so that we began officially trading these (as conditions warranted) inside the Leveraged Investing Club back in May 2018.

Now, valuation and fundamentals, it turns out, are less reliable short term indicators when selling calls.

So the set ups on our bear call spreads are primarily technical based.

PZZA (Papa John's) Bear Call Spread

Here's a good example of a Limited Upside Situation/bear call spread trade.

On Monday, 2019-09-16, we entered a PZZA OCT 18 2019 $55-$65 BEAR CALL SPREAD based on the following chart:

Based on that chart, I felt it was highly unlikely the stock would be trading at or above the $55/share level in the near term.

As of yesterday, the stock was still comfortably below $54/share - so things are still looking A-OK.

Being Able to Sell Either Side of the Market Makes Our Job MUCH Easier

Sure, we could continue being disciplined and only sell puts when we see attractive put selling set ups.

But being able to sell puts on Limited Downside Situations AND calls on Limited Upside Situations has made our job a whole lot easier.

There's also a very real self hedging aspect at the portfolio level.

Even if the market makes a move that totally surprises us, it will likely end up actually helping a number of our open trades.

(Although I don't recommend looking for any kind of mechanical approach or specific ratio to how many short put vs. short call trades you have open.)

We simply go where the best trades are at any given time.

In fact, there's a definite near term ebb and flow to the market and it's common for one type of trade to dominant for multiple weeks in a row.

It's far more common for us to enter several consecutive trades of one type or the other (i.e. selling puts or selling/trading bear call spreads) several trades in a row rather than alternating them

Again, it goes back to trading the best set ups you can find and letting the market tell you where the lucrative, high probability opportunities are.

Line of Defense #3 - Intelligent Diversification

In this section, we're going to do the unthinkable - take a page from conventional wisdom (gasp!) - and add some good old fashioned diversification into the mix.

Diversification Critique

I've long been skeptical of self serving conventional wisdom touted by the managed money industry regarding diversification.

If you want long term success as a traditional stock investor, diversification isn't necessary - or even helpful.

It's the quality of the underlying business and the valuation at which you acquire your ownership stake.

And then just stay out of the way and let the underlying business do its thing.

So why is the managed money industry obsessed with diversification?

Because diversification is the only thing that the managed money is any good at.

But diversification for diversification's sake - and the fact the bloated institutions are top heavy, inefficient, and sluggish when it comes to entering and exiting positions - is why the managed money industry consistently puts up such abysmal results year after year.

They simply have too much money under management to provide other than mediocre returns.

The more money you manage, the less practical it is to invest in terms of quality and valuation - so you end up stocking your clients/fund members accounts with a lot of mediocre investments.

And since it's an industry that pays itself based on how much money it manages vs. how well it manages that money, the message is simple:

"It's too dangerous to invest on your own and you need to own tiny, tiny, tiny pieces of lots of different businesses (even the crappy ones) rather than larger pieces of fewer, world class businesses." - Your Frenemies from the Managed Money Industry

The logic is absurd, but that's the way of the world.

If you're good at anything in life, you likely recognize conventional wisdom re: that topic or discipline for what it is - bullshit.

That said, it's still a good idea to take a closer look and see if there's some way we can employ diversification in ways that do, in fact, help us.

Is there an intelligent form of diversification we can use to make our option selling operations safer and more impregnable?

In my experience there are two helpful forms of diversification we can use when selling options.

And as we saw in the Defense Level #1 - Opening Position Size section, having massive numbers of positions - i.e. the traditional form of diversification - isn't one of them).

But let's look at two forms of diversification that can work for option sellers . . .

Diversification #1 - Diversifying Option Selling Trades by Trading Different Sectors

Because we're diversifying (but not over diversifying) with relatively small opening position sizes, we want to make sure we don't mitigate that by trading too many stocks in the same or similar sector.

Ideally, we don't want to have more than one open trade in the same sector, although on occasion, depending on the specific situation, we might end up with two.

I've also found myself in situations where I will, in fact, have two open trades in the same sector - but one is a put selling trade and one is a call selling trade.

(This doesn't happen often, of course, as a lot of stocks in the same sector tend to trade, if not quite in tandem, then in loose relationship with each other.)

Again, nothing we do here should be done mechanically.

It's not about coming up with a specific asset allocation target where we "have to" have open trades in specific sectors.

We simply continue going where the best trades are.

And if we find that there are a lot of seemingly great opportunities in one sector, we remain disciplined and trade the best one (or two?) rather than trade all of them.

Diversification #2 - Diversifying Option Selling Trades Through Time (Laddering)

There is another subtle but powerful form of diversification for option sellers:

Diversifying or laddering through time.

Laddering CDs

There's an old income strategy where you "ladder" your savings through higher yielding Certificates of Deposits (CDs) as you strive to balance between higher yielding/longer duration CDs and not tying up all your savings for years at a time.

NerdWallet illustrates CD laddering here.

- The idea is that your spread your CD durations over multiple durations so that they're expiring at different intervals

- That gives you more flexibility and doesn't tie up all your savings or capital for years at a time

- But as the longer term CDs mature and new funds are available, you roll or reinvest that into new longer term CDs with higher rates, knowing that you've got better liquidity in that more CDs are set to expire in the near term

That way you're locking in the highest yields available, but at the same time, older CDs are maturing and your money isn't all tied up for years at a time - higher rates, more flexibility, and having more reasonable access to your savings should you need it.

The Option Seller's Version of Laddering

We can do something similar - although the benefit to us isn't about generating higher returns (our annualized rates are already very high!) or improving liquidity (most of our trades have short durations to begin with).

The benefit of spreading out our trade entry dates - inside the Leveraged Investing Club we target one, sometimes two, new trades per week - is that each trade has their own unique risk-reward profiles.

A big market wide event or move won't have the same impact on a trade we entered three weeks ago vs. the one we entered yesterday.

Or the one we're going to enter next week.

And, for that matter, laddering our new trades also means that our open trades won't all have the same expiration dates either (we generally target the next monthly expiration date until that one falls below the three week threshold at which time we then move on to the next monthly expiration date after that).

Bottom line - we're not turning over and resetting our entire portfolio on a specific day every month, or expose ourselves to a single expiration date for our entire portfolio - like a reverse Wac-a-Mole, no matter how big Mr. Market's mallet is, he can't hit all our trades at the same time.

Line of Defense #4 - Never Selling Puts Remotely Near a Top

Defense Level #4 is like adding a secret safety net to your trades.

When you know there's a safety net beneath you, you can stop worrying about worst case scenarios and your capital falling to its death.

You gain the confidence to realize, hey, if I screw up, no big deal - I'm going to be just fine.

In fact, specifically when it comes to selling puts, this factor is why I'm never worried about selling options - even if a new bear market is just around the corner.

That really is one of the most common fears I hear from those who like the idea of selling options for income but still have some reservations about selling puts.

What happens if you sell puts and then the stock market suddenly crashes 30-50%?

You're going to be underwater huge and forced to take massive losses, right?

It comes down to this:

We never sell puts ANYWHERE REMOTELY NEAR a stock's top.

Value Investing Principles Stitched Into the DNA

When it comes to selling puts, while the Sleep at Night Strategy incorporates near term technicals to help us time our entries, that's only one part of it.

The Sleep at Night Strategy has core value investing principles stitched into its DNA.

Ours is very much a value investing oriented trading strategy, not a momentum, priced to perfection, high growth stock trading strategy.

I cover selling puts on value stocks vs. growth stocks in depth in Chapter 3 of my Complete Guide to Selling Puts.

Here's the takeaway - by the time we sell a put on a stock . . . much, most, or all of the damage is already done.

(And the near term technicals we use have been very effective in helping us get a good feel for when the worst is over.)

The significance of this really can't be overstated.

Ben Graham, the Father of Value Investing himself, used valuation as his core margin of safety advantage in the stock market.

After the crash of 1929, when he'd had his ass handed to him like everyone else, he scoured the financial markets looking for assets that were trading below his calculation of their intrinsic value or true worth.

Those are the key principles of value investing - acquiring assets for less than their true worth, and ideally never losing money on an investment.

Graham's form of value investing was designed to protect an investor against future bear markets and market crashes.

In fact, it would be kind of absurd to hear an investor say, "I'm drawn to value investing, but I worry what would happen during the next bear market."

Since we're basically replicating the same value investing process into our put selling trades (actually, we're improving that process substantially as we'll see in the next section), once you truly recognize what we're doing here, it's just as absurd to view this form of put selling as anything other than low risk.

Examples - Selling Puts on Value Investing Situation (and Nowhere Near a Top)

BWA (BorgWarner Inc.) - Classic Value Play

Here's a great example - check out this chart that tells the whole story:

Back in early August 2019, BWA:

- Had already fallen about 20% from its recent highs

- Was technically oversold

- Had just bounced off a key support level

- Saw its MACD Histogram (the blue bars behind the MACD) begin to rise (a confirmation/timing indicator we've had a lot of success using)

And the stock was also trading at less than 9 times next year's estimated earnings.

Selling Puts at Bottoms vs. Tops

In the event of a global recession, sure, there would obviously be more downside, but at the same time, it was no accident that we sold puts on the stock when it was trading in the low $30s vs. the low $40s.

As investors, we scare ourselves (or allow the financial media to scare us) by measuring bear markets and crashes in terms of extremes - from highest peak to lowest trough.

But even if we get on the wrong side of a trade, there's simply no way we ever come close to exposing ourselves to the maximum pain that's theoretically possible.

And how did the BWA put selling trade turn out?

On August 9th 2019, I sold or wrote (2) SEPT 20 2019 $32.50 PUTS for $1.02/contract.

(And collected $203.70 after commissions on a $6500 cash secured capital base).

Fast forward 42 days and BWA closed at expiration @ $36.77/share and the $32.50 short puts expired worthless and we achieved our full profits.

That worked out - using my favorite metric - to be a stellar 27.23% annualized ROI over that nice, extended 42 day holding period.

(This was also one of 62 - and counting - profitable trades we've booked inside the Leveraged Investing Club YTD 2019 against zero booked losses.)

Again, this is such an important point, I really feel the need to underscore it by repeating it:

When we sell puts - by the very nature of our trade selection and set up process - we NEVER sell those puts at anything close to a top.

Example of Bad Put Selling Set Up on High Quality "Defensive" Stock

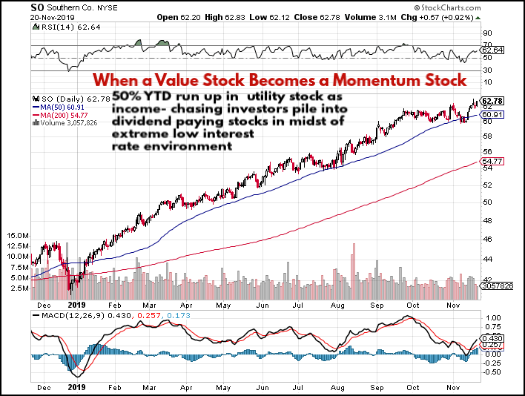

Finally, let's take a quick look at this value investing component to selling puts from a slightly different angle.

We often think of value stocks vs. growth stocks in terms of sector. Take consumer staple type stocks and utilities.

Those certainly aren't what would typically be considered growth stocks.

But that doesn't mean they're automatically always value stocks.

When "Value" Stocks Get Expensive

In the fall of 2019 - when I'm writing this - consumer staples and utilities are actually fairly expensive.

Or said another way, at the very least, a lot of them have had big run ups this year.

That's thanks to an interest rate environment that's been falling and is now super low so that income investors have been bidding quality dividend paying stocks higher and higher.

Case in point:

There's no way at present I would sell puts on these stocks no matter how great the short term technicals looked.

They've just run up way too over the course of the year.

Great underlying businesses, to be sure, but potentially a lot more downside risk in their share prices than upside potential at this point.

And that's hardly an inviting put selling situation.

Line of Defense #5 - Trade Management and Repair

The Sleep at Night High Yield Option Income Strategy is not simply about hunkering down and weathering a storm if something bad happens.

Yes, our focus in this article has been on building multiple DEFENSIVE layers into your trades.

But we have other - more offensive related - resources as well.

There's that great line in the film, HellBoy where Professor Bruttenholm (played by the late John Hurt) says:

"There are things that go bump in the night . . . And we are the ones who bump back."

So we'll close this series by talking about how we can go about landing some body blows on Mr. Market vs. simply dodging his.

Fighting Back with Our Trade Repair Process

One of the most powerful ways that our Sleep at Night High Yield Option Income (option selling) Strategy is customized is in how we manage - and if necessary - repair our trades.

Up until this point in this series, everything has been about constructing our trades to minimize the potential damage that can be inflicted on us.

And most of the time that's all we need to consistently do very well for ourselves.

But sometimes, despite our precautions, a trade will still move against us, giving us the opportunity to dig a little deeper into our bag of tricks (and pull out a pair of brass knuckles).

Our Twin Objectives on "Bad" Put Selling Trades

We have two objectives anytime a trade moves the wrong way on us and trades in the money.

(e.g. We "insure" a stock at the $50/share price by writing or selling a put at the $50 strike price and then the stock trades below $50/share.)

- We always want to collect a net credit on every roll or adjustment we make

- We also want to work the strike price lower on the position whenever possible

Same idea works on short call/bear call spreads that go against us.

In that scenario, we want net credits and to work the strike price higher whenever possible.

That's our one-two punch combo when selling puts.

The more we work the strike price lower, the less the stock has to "come back" in order for us to be out of the trade.

And the more net premium we collect over the life of the campaign, the greater our final profits will be.

(When we talk about repair, it's never about merely breaking even or somehow just limiting the damage - it's about still walking away with profits when all is said and done.)

The Power of Net Credits and Selling Time Value

We'll work through some examples in a sec, but let's make sure we're on the same page re: the concept of net premium or net credits.

You initially sell or write a put and collect a cash premium payment up front, and as long as everything goes according to plan, it's easy money.

But if the stock misbehaves and sells off so that the share price is now below the strike price of your short put, you've got three choices:

- Allow the put to be assigned at some point and accept delivery of the shares at the agreed upon strike price

- Buy back your short put for a loss

- Manage/Repair the trade

My preference is always that last one.

And rolling for a net credit simply means that you collect more premium for selling/writing the new put than what it costs you to buy back or close the old put.

If it costs me $3.00/contract to buy back an expiring put at a certain strike price but then I collect $3.50/contract for selling a new put at that same strike price but for a later expiration date . . .

Then I just rolled my short put for a $0.50/contract net credit.

OPTION PRICING 101

Now this is the key to everything - the farther away a strike price is from the underlying stock's current share price, the less time value there will be for that option.

In other words, the best net credits will always be at strike nearest the current share price.

And the opposite is always true.

The more the stock moves against your position, the less time value there will be available for you to exploit on your future rolls and adjustments.

So there's a bit of an art to this.

And math, of course.

The customized and proprietary 4 Stage Short Put Trade Repair Formula that I developed and fine tuned over the years takes the guesswork out of what adjustment to make and the optimum time to make it.

And it's been amazingly effective over the years.

Let's look at some examples . . .

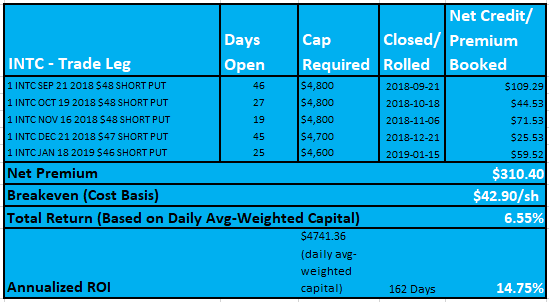

REPAIRED PUT SELLING TRADE #1 - INTC @ 14.75% Annualized ROI Over 162 Days

Here's the Final Trade Performance Table for this one:

- Original Position = $48 Short Put

- Stock sold off and would eventually trade into the low $40s

- I rolled the $48 short put straight out (to the same strike) for net credits twice

- On the 4th leg of the trade I was able to roll down and out to the $47 strike for a net credit

- On the 5th and final leg of the trade I was able to roll down and out again - this time to the $46 strike - for a net credit

- At that point, the stock had rebounded enough that I was able to exit the trade outright and with all my accumulated net premium (original premium collected plus net credits generated along the way) as my final booked gains

- I booked $310.40 of final profits on a daily average-weighted cash secured capital base of $4741.36, or a very respectable 14.75% annualized return over 162 days

- Because I worked the strike price from $48 to $46, the stock never had to come back to the original $48 share price

- And when you factor in the accumulated net premium along with the lower strike price, my final cost basis or breakeven on the trade was $42.90/share (on a trade that I originally "insured" or theoretically offered to buy the stock at $48/share).

That's the one-two counter punch combo:

>> With my left hand jabs I kept piling up net credits every time I touched the trade

>> And with my occasional right hand roundhouse, I completely changed the strike price to my continued advantage

REPAIRED TRADE #2 - AN (AutoNation) @ 15.23% annualized over 149 days

Check out the Final Trade Performance Table for this trade:

- I originally sold a single AN put at the $52.50 strike and same story as with the first example - the stock sold off instead and the game was on

- Again, every roll or adjustment produced a net credit

- And this time, over five legs/rolls, I managed to work the strike price from $52.50 all the way down to $48

- Final booked returns were $450.25 on an average daily capital base of $7243.29, or another very respectable 15.23% annualized ROI over 149 days

- And the final cost basis/breakeven on the trade was all the way down to $43.50/share (that's some serious downside protection on a trade that originated at the $52.50 strike)

Imagine how much safer Ben Graham could've made his investments if he'd had access to selling options like we do.

Graham was so careful and conservative because he knew his cost basis was static - his cost basis was whatever he paid for his investment on the open market.

The only way he could make positive returns - and to protect himself from losses - was if the value of the asset in question rose in price.

Fortunately for us, we don't labor under the same restriction.

As option sellers who can continue to roll, adjust, and otherwise manage an option selling trade indefinitely (or as long as it's in our advantage to do so), our cost basis is dynamic, not static.

Every time we touch a trade, the cost basis and breakeven improves for us (adjusted downward when selling puts and adjusted higher when selling calls/bear call spreads).

Mr. Market the Underdog

To summarize . . .

>> We can construct our trades with multiple layers of protection

>> And - with our ability to repeatedly sell additional time value and, in the process, create a dynamic cost basis that we continually move in our favor - we can also take the fight to Mr. Market when we need to

You know what that makes Mr. Market?

A serious underdog.

How is This Possible and Not One of Those Too Good to be True Things?

At the end of the day, this is about trade offs.

Theoretically, stock only investors - and buyers of options, for that matter - have more potential upside than we sellers of options do.

When they get on the right side of a trade, they can generate some pretty hefty returns.

But . . . they can't afford to be wrong because there's no downside protection built into their trades and investments.

If they're wrong, they're going to lose money, plain and simple.

And - especially when we're talking about buyers or net buyers of options - these can be heavy losses.

The trade off for option sellers who learn to build maximum protection into their trades is the requirement that we take potential monster returns off the table.

But get this . . .

Because options are leveraged instruments, our super safe returns are still usually very good.

It's just that they're never going to be monster returns.

We target 15-25% a year no matter what the broader market does.

In 2018, inside the Leveraged Investing Club we booked 17.12% gains vs. the S&P 500's 6.2% full year loss.

In 2019 - fingers crossed - we're on pace to do about 20%.

And that's a trade off I'm more than happy to make.

Multiple Lines of Defense Review

It truly is possible to construct your put selling trades - or rather option selling trades since I really do believe you should consider the flexibility of selling either/both sides of the market as conditions warrant - with multiple lines of defense.

When approached this way, you not only ensure that you'll always be able to find attractive high yield income set ups, but your portfolio will be much, much safer than all the other portfolio's out there that "need" a stock to behave in a certain way or else losses result.

So to quickly review the multiple lines of defense you can add to your own option trading castle . . .

- Option Selling Line of Defense #1 - Relatively Small Opening Position Sizes - the smaller a position, the easier and more effective contract expansion is in the repair process (even though only about 5% of our trades ever require additional capital, because we don't know in advance which one trade out of twenty will require this little helping hand, we structure every trade as though it could be the one)

- Option Selling Line of Defense #2 - Trading Both Sides of the Market - when you can sell puts on stocks that won't trade lower AND sell calls on stocks that won't trade higher, you not only have great trading opportunities in every market environment, you also naturally hedge your own portfolio

- Option Selling Line of Defense #3 - Traditional Diversification (Done Right) - we use two forms of sensible and effective diversification - diversifying by not over concentrating in any one sector, and diversifying by time by staggering or laddering new trades with different trade entry and exit dates

- Option Selling Line of Defense #4 - Never Selling Puts Anywhere Near a Top - simply by the nature of our trade selection and set up criteria, we never sell puts anywhere remotely near a stock's top (or calls anywhere remotely near a stock's lows) - by the time we enter a put selling trade, most if not all of the carnage is already done (or most if not all of the run up has already occurred when we sell a call/bear call spread)

- Option Selling Line of Defense #5 - Trade Management and Trade Repair - with our highly effective 4 Stage Short Put Trade Repair Formula (applicable to in the money short call/bear call spread positions as well), we can handle just about anything Mr. Market throws at us as each time we touch a trade the breakeven/cost basis on it improves and we can continue this process indefinitely

Tweet

Follow @LeveragedInvest

HOME : Selling Puts : Constructing Multiple Lines of Defense Into Your Put Selling Trades

>> The Complete Guide to Selling Puts (Best Put Selling Resource on the Web)

>> Constructing Multiple Lines of Defense Into Your Put Selling Trades (How to Safely Sell Options for High Yield Income in Any Market Environment)

Option Trading and Duration Series

Part 1 >> Best Durations When Buying or Selling Options (Updated Article)

Part 2 >> The Sweet Spot Expiration Date When Selling Options

Part 3 >> Pros and Cons of Selling Weekly Options

>> Comprehensive Guide to Selling Puts on Margin

Selling Puts and Earnings Series

>> Why Bear Markets Don't Matter When You Own a Great Business (Updated Article)

Part 1 >> Selling Puts Into Earnings

Part 2 >> How to Use Earnings to Manage and Repair a Short Put Trade

Part 3 >> Selling Puts and the Earnings Calendar (Weird but Important Tip)

Mastering the Psychology of the Stock Market Series

Part 1 >> Myth of Efficient Market Hypothesis

Part 2 >> Myth of Smart Money

Part 3 >> Psychology of Secular Bull and Bear Markets

Part 4 >> How to Know When a Stock Bubble is About to Pop