Repairing Naked Puts:

Why Stick with a Losing Trade?

Question - I am interested in your "repair strategy." I would like to know when you have a trade which has "gone south" why rather than stay with the same underlying stock, you do not consider cutting your losses in the current trade, and rather than rolling out by selling a put in the same stock at a later date, you do not consider selling a put in another stock to cover your losses or try for a profit in another trade?

I have been selling puts for several years and have usually received a premium when the trade expires or have meekly been assigned the stock which was always one I had previously decided I would not mind owning. But I have been hurt by this market rout. Thanks for your always informative thoughts and I would appreciate your answer. All the best. B.N.

Answer

Thanks for the question and for reaching out. It's a great question and one I get fairly often.

So there are a number of reasons why I stick with "losing" short put trades and repair them vs. just cutting my losses.

- First, cutting losses early is a little easier said than done. By the time you realize you have a problem, the loss you would incur will likely be a multiple of the amount of premium you collected up front to begin with.

So that means it's going to take multiple successful, no drama trades in the future to offset those losses, and that's just to get back to breakeven.

- Second - and I don't mean this to sound flippant or anything - but why accept a loss when you don't have to? After you've successfully repaired a few in the money short put trades, and after you understand the mathematical principles involved, the process gets less scary or mysterious.

That doesn't mean there's no emotional toll involved. It's still very easy to get that sick, sinking feeling when - as you say - the trade goes south on you.

You may have already seen the article I posted where I addressed the emotional impact of trade repair (or "how not to feel like crap when sticking with an underwater trade"), but here's a link in case you haven't:

But again, once you're able to re-categorize this as a mathematical problem rather than a financial threat, it's a much easier process to handle emotionally.

- Third, when I talk about repair or renegotiation or rehabilitation, I'm not simply talking about getting back to breakeven.

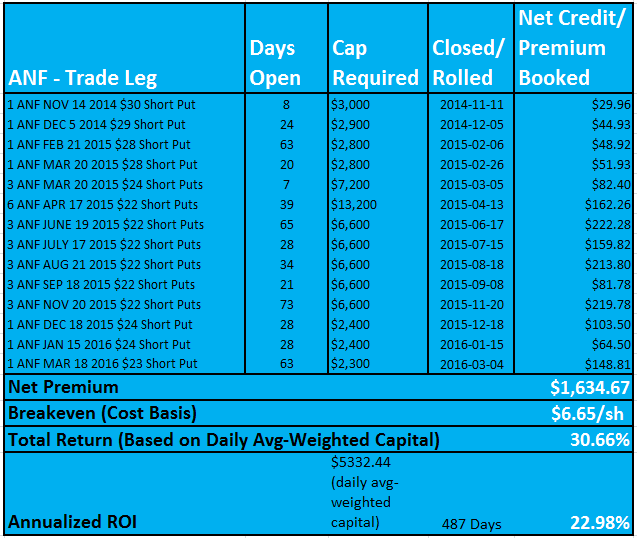

The returns sometimes might not be much more than a few percentage points on an annualized basis (or in the case of the ANF trade - see below - they might in fact end up being very lucrative). In any case, the point is that I always shoot for POSITIVE gains at the end of the day. The goal is to - once all the dust has settled - walk away with more money than I started with.

Or as I say, even a paltry gain is bigger than a big fat loss.

Opportunity Costs of Reparing Naked Puts

But let me play devil's advocate to myself here for a moment.

There can definitely be an opportunity cost to sticking with and repairing an in the money short put position.

I remember in 2014, I fell for a false breakout in EBAY and basically ended up selling puts at the top. I was much less efficient with the trade repair process back then (more about that below) and as a result, I ate up a lot of two very important resources - capital and time.

In fact, there were several really great trade ideas I identified and wrote about inside The Leveraged Investing Club at the time that I was unable to enter myself because the portfolio's capital was being used to repair that damn EBAY trade.

So I ended up making a net $869.39 over the entirety of the trade which was much better than any kind of a loss, of course, but as I say, it ate up a lot of capital, required 163 days, and resulted in pretty modest 6.17% annualized overall returns.

I don't think that's an indictment of the trade repair process, however. But it does show that the process needed to be more efficient and that trade selection and set up is also very important.

4 Stage Short Put Trade Repair Formula

Now, re: the actual repair process, we have a four stage process (aptly named The 4 Stage Short Put Trade Repair Formula).

The above link prvides more details.

But from a big picture perspective, let me share with you a mathematical principle as a starting point that may make you think about managing short put trades a little differently.

And that's the idea that - if you have unlimited capital, and assuming the underlying stock doesn't trade down to zero - there's no reason to ever lose money selling puts.

Obviously no one has unlimited capital (at least I don't), but what's important here is the mathematical reasoning behind that statement. And probably the best way to illustrate that is to use a real world example.

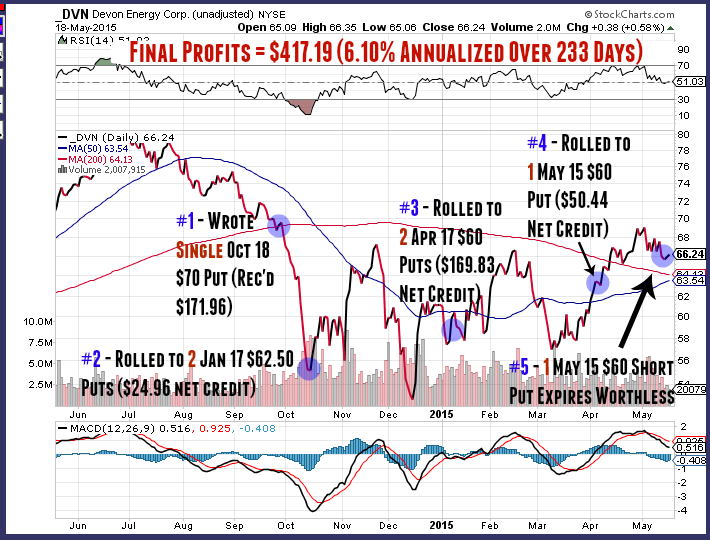

DVN - Making Money Selling Puts on a Falling Stock?!?

So back in the fall of 2014 - having been caught by surprise along with just about everyone else by the energy sector collapse - I wrote a single $70 put on DVN.

And then, before I know it, the stock is trading down in the mid-$50s.

Yikes - a personal tragedy, right?

Except that it wasn't. It was actually a gift and led to a major ah-ha! breakthrough.

With the stock trading @ $54.06, I rolled (or converted may be a better way of looking at it) my single, deep in the money $70 short put out 3 months to 2 short puts at the $62.50 strike for a very, very small net credit (lol - although it still easily beat current money market rates).

- BTC (1) October 18 2014 $70 Short Put

- STO (2) January 17 2015 $62.50 Short Puts

- Collected total net premium of $24.96 after commissions

- Expanded # of contracts from 1 to 2

- Cash-secured capital requirements increased from $7K to $12,500

- Strike price decreased from $70 to $62.50

- Breakeven decreased from $68.28 to $61.52

From an accounting angle, this is important. I'm not sure how you track, record, or conceive of your short put positions, but I see mine as campaigns or series of trades vs. one-time events or as separate trades.

And when I make an adjustment, I roll the cost of closing out the old or expiring leg into the proceeds of the new leg.

And I always strive to generate a net credit on any move I make - that lowers the breakeven on my trade, even if by only a small amount.

So in this example, I was able to convert a single $70 short put into 2 short puts at the $62.50 strike while increasing my portfolio's cash balance, modest though it may have been.

The big impact on the breakeven wasn't from the net credit, however - it was the result of dramatically lowering the strike price on my short put position from $70 to $62.50.

In one move, my breakeven went from $68.28/share (100 shares at the $70 strike price less the initial premium received of $171.96 divided by 100 shares) all the way down to $61.52/share (200 shares at the $62.50 strike less the accumulated net premium collected of $196.92 divided now by 200 shares).

Yes, I expanded the trade. but what situation is more risky? With the stock trading @ $54.06, would I rather be on the hook for 100 shares at $70/share or 200 shares at $62.50/share?

And this is a dynamic process - my breakeven (or cost basis if assigned) - is something that I can repeatedly lower over time.

You can probably see where I'm going with this - theoretically we could continuously expand the number of contracts as a way of continuously lowering the strike price on a short put position.

And as long as A.) the stock eventually bottoms (at a price that's above zero) and B.) we don't run out of capital, there's no reason we would ever have to accept a loss against our will

The "Double-Half Principle"

Now I'm not suggesting we blindly expand a trade indefinitely because if that's our approach, there's a good chance that we're going to find ourselves in a situation where our capital runs out before our repairs are complete.

And at that point, we really will be stuck with a loss - or at the least, a lot of dead money waiting for the stock to "come back" to a specific non-dynamic price point.

But it's important to recognize what I call the "Double Half" principle and how it relates to the intrinsic value of a short DITM put option. And what I mean is that by doubling the number of contracts in a short put position, I can effectively cut in half the distance between the strike price of my current position and the current share price of the stock.

For example, a single short put that's $10/contract in the money has $1K of intrinsic value. Well, so does 2 short puts that are $5/contract in the money. With a $50 stock for example, 2 $55 puts has the same amount of intrinsic value as 1 $60 put.

Ultimately, we have two objectives when we're working with in the money short puts - as I mentioned earlier, ideally we want to generate a net credit on any adjustment we make. And we also want to lower the strike price on our position as often and as much as possible.

(And arguably a third objective as well - we don't want to have to roll out ridiculously far away to achieve either of our first two objectives).

Putting It All Together

Now I had a lot of individual tricks and techniques to achieve these objectives, but it wasn't until DVN crashed on me and I saw that in that case simply adding 1 contract to the position enabled me to lower the strike price by $7.50 that I realized how powerful this principle really was.

Here's a chart that tracks the series of trades and final results:

Remember the EBAY trade I talked about earlier? Yes, I repaired that one, but I expanded the trade aggressively once it first began moving against me. I basically found myself in a foot race with Mr. Market and while he didn't run that far - I think the stock probably fell 10-15% total - by the time I caught up with him I had close to 80% of the portfolio's capital dedicated to that single trade.

Crazy in hindsight.

The DVN experience really opened my eyes and I saw how the individual techniques I had been using to engineer the strike price lower and lower could be used together, sequentially, kind of like layers of defense.

Right and Wrong Ways to Repair Underwater Naked Puts

Trade expansion, for example, is a very powerful technique - when timed correctly. But use it too soon, and it's a resource that's quickly depleted.

So now we don't even look at adding contracts to an underwater position until Stage 3 of our 4 Stage process, and delaying contract expansion is really brilliantly effective if I do say so myself (I feel more like I've discovered this rather than created or invented it) for three reasons:

- It helps us preserve our capital and prevent us from overleveraging during the repair process (as I did with the EBAY trade).

- It gives us more bang for our buck by allowing us to make larger strike price adjustments.

- It also gives the stock ample time to bottom.

That last one is a subtle but powerful advantage. Stocks don't fall forever, especially stocks of sound businesses. An underlying business may be facing headwinds, but as long as we're confident that the business itself will remain profitable and solvent, there's a limit to how far Mr. Market can push it down.

It should be noted that commodity price sensitive trades - selling puts on energy stocks, for instance - can extend a declining stock farther and for longer time periods because the issue is much more about the dynamics of the commodity rather than the operational execution of the underlying business.

My ANF trade, for example - there was no doubt the business was troubled and had a lot of work to turn itself around. At the low point, the stock fell an incredible 49.94% from my original entry point (and it had already fallen a great deal before I ever entered it as well).

But I never had any doubts about Abercrombie's survival because the business remained firmly profitable - just not as profitable as it had been or as much as investors wanted.

And it this case, the implied volatility levels were also so high, that the repair process was easy - and lucrative - to manage.

At the point of repair, the position had generated a 17.59% annualized return and I never had to expand the trade to a ridiculous or unsustainable level.

Once the repairs were completed, I remained with the trade in order to really start ringing the register - and only reluctantly exited the position after the stock had begun rebounding rather significantly and I didn't want to start chasing it in the other direction and undo all the good work I'd accomplished.

So when I finally walked away, I did so with impressive 30.66% total returns, or 22.98% annualized over 487 days.

And get this - during the same holding period - between November 3, 2014 and March 4, 2016 - the S&P 500 actually fell 17.82 points, or a negative 0.88%.

So in this case, sticking with a "losing" trade enabled me to outperform the broader market by more than 31 percentage points.

Conclusion

Whew!

OK - hope that helps to answer your questions and gives you some interesting ideas to ponder.

This is as much math based as it is investing based, but we're not talking advanced mathematics at all.

Still, until you've either used the 4 Stage Short Put Trade Repair Formula yourself (the full write up and explanation is included in the foundational Sleep at Night High Yield Option Income Course inside The Leveraged Investing Club) or seen real world examples of it being used, it may be difficult to conceive of how effective it can be.

I've actually had members join the Club primarily for the training on the 4 Stage Trade Repair Formula.

Again - hope this helps. If you have more questions, don't hesitate to ask (I promise to try to be briefer next time!).

Take care -

Brad

UPDATE: I would later re-enter the trade a few months later after the stock pulled back again and logged a 27.80% annualized return over 85 days, but I haven't sold another put on ANF since.

Somewhere along the way, it finally became questionable whether the company was capable of being consistently - or meaningfully - profitable.

Great run or not, business is business, and I don't insure (i.e. sell puts on) businesses that can't turn a profit.

Tweet

Follow @LeveragedInvest

HOME: Trading Stock Options FAQ: Why Stick With Losing Trades?

>> The Complete Guide to Selling Puts (Best Put Selling Resource on the Web)

>> Constructing Multiple Lines of Defense Into Your Put Selling Trades (How to Safely Sell Options for High Yield Income in Any Market Environment)

Option Trading and Duration Series

Part 1 >> Best Durations When Buying or Selling Options (Updated Article)

Part 2 >> The Sweet Spot Expiration Date When Selling Options

Part 3 >> Pros and Cons of Selling Weekly Options

>> Comprehensive Guide to Selling Puts on Margin

Selling Puts and Earnings Series

>> Why Bear Markets Don't Matter When You Own a Great Business (Updated Article)

Part 1 >> Selling Puts Into Earnings

Part 2 >> How to Use Earnings to Manage and Repair a Short Put Trade

Part 3 >> Selling Puts and the Earnings Calendar (Weird but Important Tip)

Mastering the Psychology of the Stock Market Series

Part 1 >> Myth of Efficient Market Hypothesis

Part 2 >> Myth of Smart Money

Part 3 >> Psychology of Secular Bull and Bear Markets

Part 4 >> How to Know When a Stock Bubble is About to Pop